A Modern Look at Dilophosaurus

In this video we’ll travel back to the world of the early Jurassic and take a modern look at it’s most iconic dinosaur: Dilophosaurus. By studying the latest specimens, fascinating fossils from the world Dilophosaurus lived and evolved in, and modern biology, paleontologists are just now starting to get a clearer picture of this important period in dinosaur evolution and the history of our planet.

This video is the culmination of about 5 years of communication and collaboration with Dr. Adam Marsh who has been studying Dilophosaurus for the past 6 years, and who recently published this comprehensive description of this important dinosaur. You can download Adam’s scientific paper for free here:

A comprehensive anatomical and phylogenetic evaluation of Dilophosaurus wetherilli (Dinosauria, Theropoda) with descriptions of new specimens from the Kayenta Formation of northern Arizona

Over the last several years I have had the good fortune to be able to create numerous pieces of art centered around Dilophosaurus and the world it evolved in thanks to the St. George Dinosaur Discovery Site and The Las Vegas Natural History Museum which have commissioned me to create numerous pieces of art depicting life in the early Jurassic, and I have jumped at every opportunity to explore these fossil sites in person because there is still so much to be discovered in the early Jurassic.

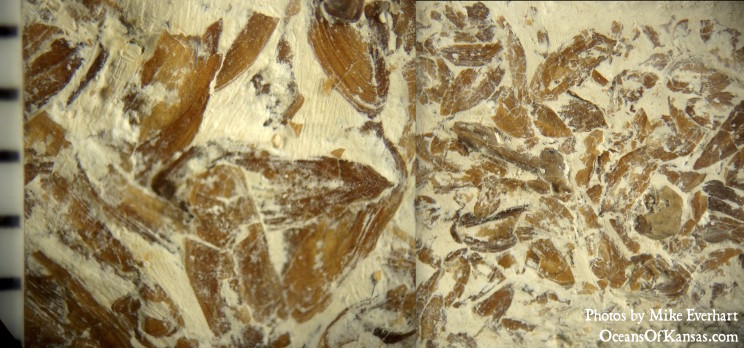

At the St. George Dinosaur Discovery Site there are amazing trackways from a few million years before Dilophosaurus that show us that large theropods were in fact swimming in a lake. A vertebrae discovered at the site – which is now being described by Adam and Andrew – shows us that at least some of the animals at the site were close relatives of Dilophosaurus. You can see a clip from the St. George Dinosaur Discovery Site of Dr. Jerry Harris interpreting the find here, with special mention of the thinly laminated bone & air sacs:

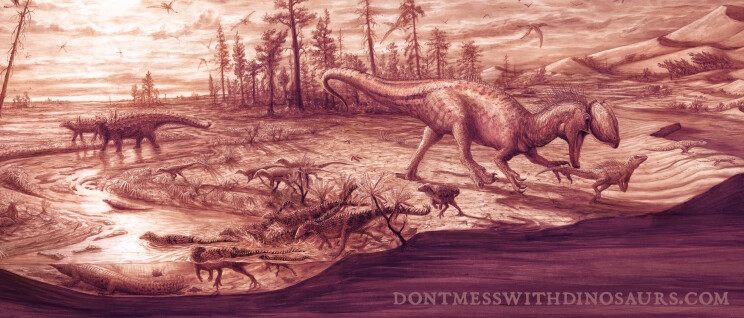

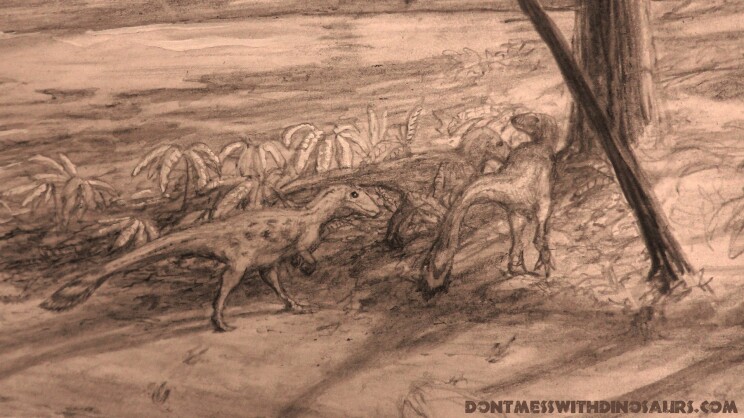

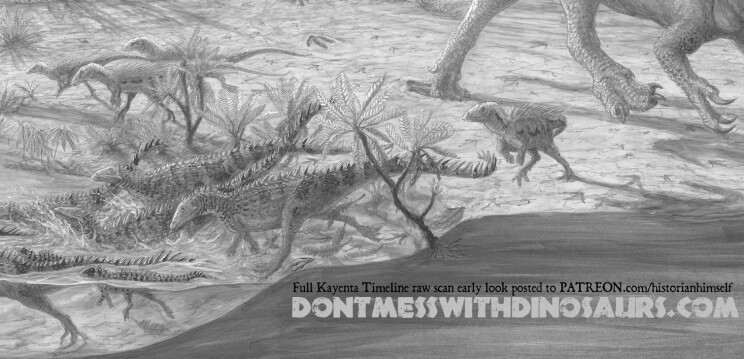

Nearby, both in southwestern Utah and just over the Border in Nevada there are EXTENSIVE outcrops of late Triassic and early Jurassic rocks that have yet to be explored by paleontologists. When Andrew Milner (SGDS) was called upon to do a paleontological survey of an area where a road was to be constructed, he and his museum volunteers found HUNDREDS of fossils of tracks, various teeth, and plants at several levels in the Kayenta Formation. These awesome finds will be featured in upcoming scientific publications and displayed in an upcoming Kayenta Timeline exhibit alongside my Kayenta Timeline illustration featured above and in my video. Every one of these Kayanta intervals is filled with details drawn directly from the fossil evidence from Kayenta fossil sites, with a heavy focus on those uncovered by Andrew and his crew at these sites.

You can see a time lapse of 1 hour of work on the Kayenta Timeline here:

For more information and to support these museums as they embark on ambitious projects in the face of the COVID-19 shutdown, please visit their websites:

Las Vegas Natural History Museum

https://www.lvnhm.org/support

Saint George Dinosaur Discovery Site

https://utahdinosaurs.com/get-involved/

I would not have had the opportunity to work for either museum if it weren’t for paleontologists Andrew Milner (SGDS) and Dr. Josh Bonde (formerly at LVNHM) vouching for me. Many thanks to Andrew and Josh for recognizing the detail I put into my work, and to museum directors Diana Azvedo (SGDS) and Marilyn Gillespie (LVNHM) for hiring me to do these exciting paleoart projects.

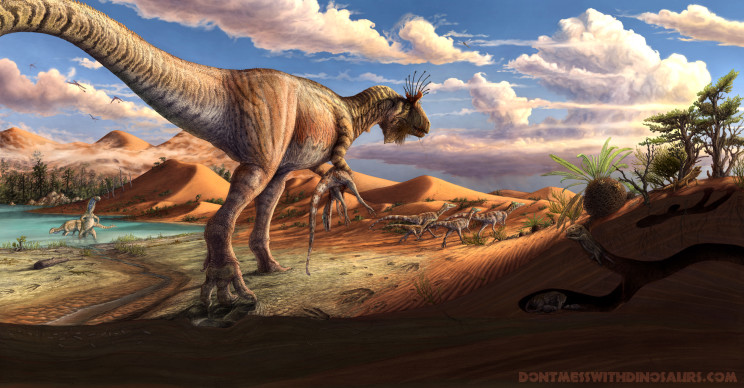

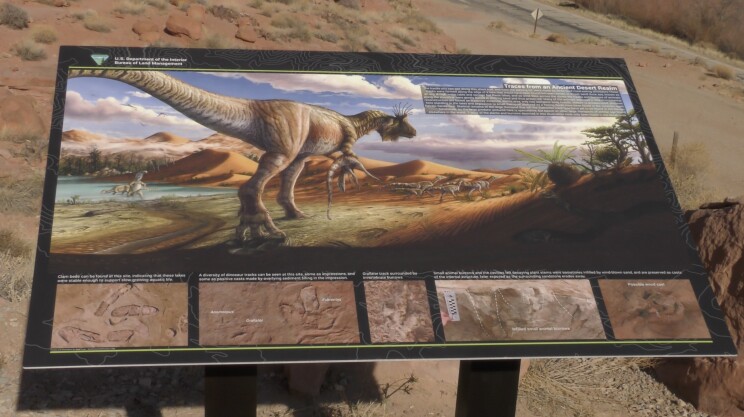

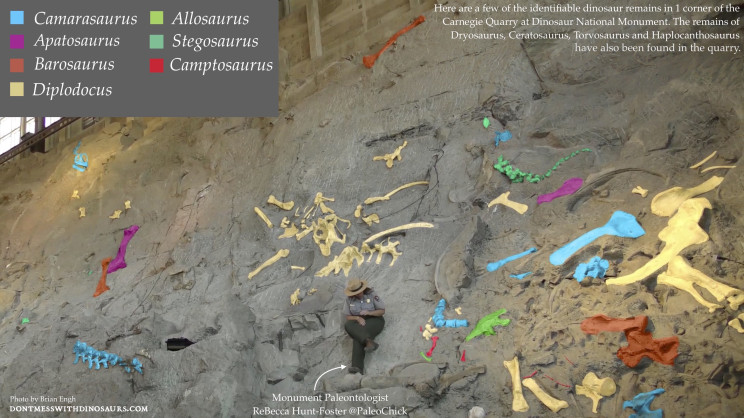

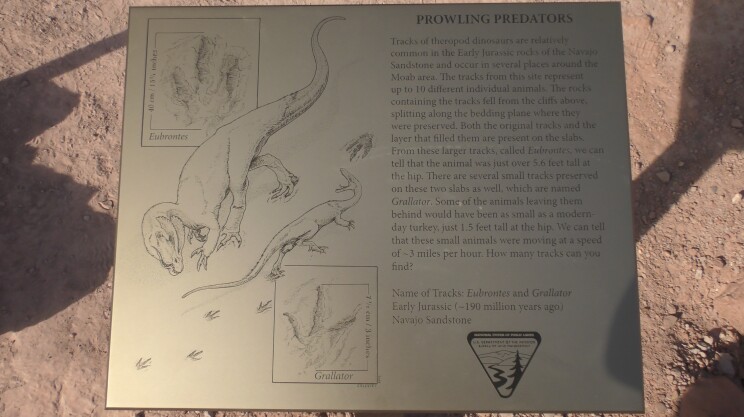

My Modern Look at Dilophosaurus video also features art commissioned by paleontologist ReBecca Hunt-Foster through funding from Utah BLM / Utah Friends of Paleontology. The scene depicting an early Jurassic tracksite was created for an interpretive panel now at the Poison Spider Dinosaur Tracksite near Moab Utah. You can explore this fascinating early Jurassic tracksite (for free) on your public lands near Moab Utah. More information here:

https://www.discovermoab.com/dinosaur-museums-and-hikes/

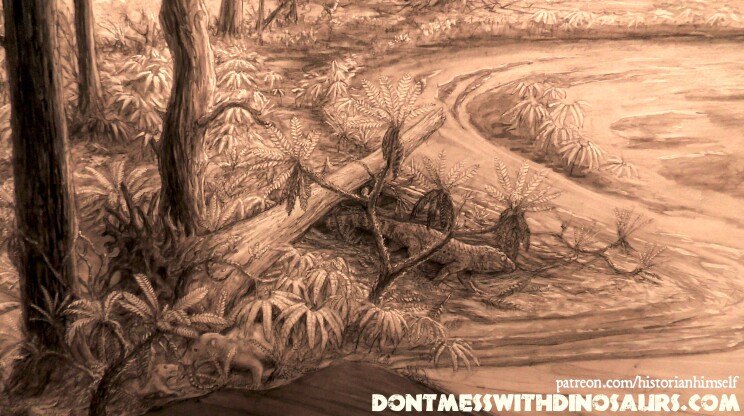

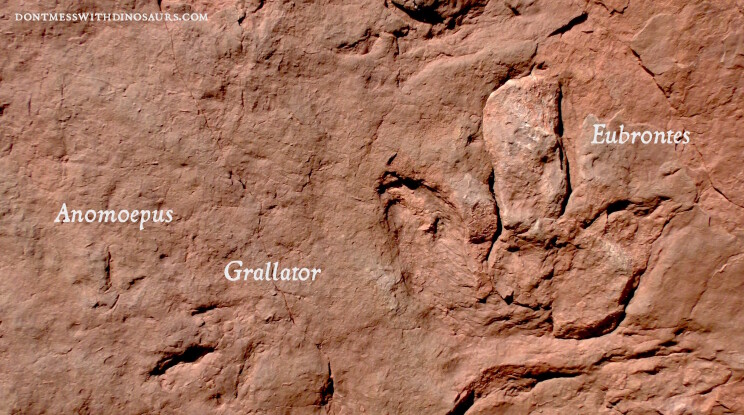

For those that can’t make the visit: the tracksite preserves a variety of tracks from early Jurassic animals along the shore of a lake that had formed in the middle of a dune field. If you look closely at my art you can make out many of the track makers: from tiny insects and protosuchid crocs, to early mammal relatives and, of course, various theropod dinosaurs.

The site also features signs with interpretive art by the great Matt Celeskey

The late Triassic scene featured in the above video is a work in progress, also commissioned by ReBecca/UFOP for another tracksite on the edge of the Bears Ears National Monument. The tracksite is called the Shay Canyon Tracksite and features a bunch of tracks of primarily non-dinosaur weirdos from the Triassic. The animals in my art are reconstructed after skeletal finds from Petrified Forest, and several Utah Sites being excavated by Randy Irmiss and Andrew Milner.

The end Triassic extinction, and the recovery of earth’s ecologies that followed in the early Jurassic is a really important time for our species to study & understand because it relates directly to climate change. Data from geology, paleobotany and paleontology suggests that a huge catestrophic extinction that ended the Triassic period was brought about by a sudden increase in atmospheric CO2 which cause runaway global warming and ocean acidification. While the CO2 spike at the end of the Triassic was caused by volcanic eruptions in what is now the central Atlanic which cooked through a bunch of marine carbonate rocks and released the vast amounts of CO2 stored in them, the latest data indicates that the rate of CO2 flooding into the atmosphere at the end of the Triassic was about the same as the rate at which humans are flooding the atmosphere with CO2 by burning carbon-rich fossil fuels. This is really really scary. You should be shook. This extinction wiped out many of the most badass rugged, gnarly, armored prehistoric monsters that have ever lived, and which had thrived all over the planet for millions of years when the extinction took place. Here are a few links to get you started on your journey of understanding extinction and the role we play in it:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Triassic%E2%80%93Jurassic_extinction_event

https://ucmp.berkeley.edu/seedplants/ginkgoales/ginkgofr.html

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1342937X13003043