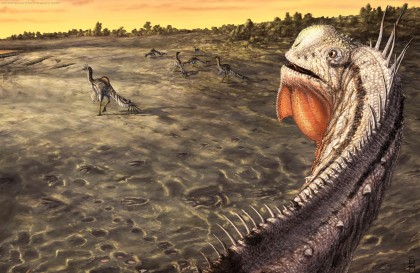

YO. NEW SPECIES OF DINOSAUR. RIGHT HERE.

Aquilops americanus, a new species of basal ceratopsian dinosaur.

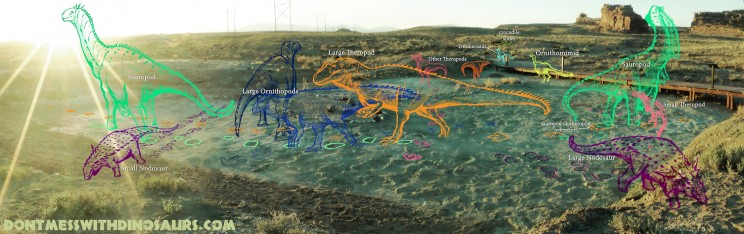

Click HERE for a “field guide” to everything in the above image.

For an overview on the new species and it’s significance head over to Andy Farke’s blog post at PLOS, and/or check out the paper. For a rundown on Matt Wedel’s involvement in the story of Aquilops’ check out his blog post at SV-POW, and stay tuned for his post about reconstructing the skull. Here on DMWD I’m gonna talk about how we went from a few squashed noggin bones to all the stuff you see in these here color pictures.

The journey that lead to the above illustration all started a while back when the world’s two most powerful paleontologists/galactic warriors, Andy Farke and Matt Wedel, hit me up about illustrating a new species of dinosaur they were working on publishing. Basically they were like, “We have the only known remains of a creature nobody’s seen in 106 million years and we want you to be the first guy show people how it might’ve looked, which will help us explain to people why it’s so goddamn awesome.” To me it was the paleontological equivalent of getting asked to combine forces with Jackie Chan and Jet Li to make a kung fu movie with crazy stunts in it, but I didn’t even have to get kicked repeatedly in the neck or thrown through a bunch of panes of glass, i just had to light fireworks and blow stuff up all around them to help make them look extra good while they kick the shit out of all the badguys who hate science and dinosaurs.

So I said yes.

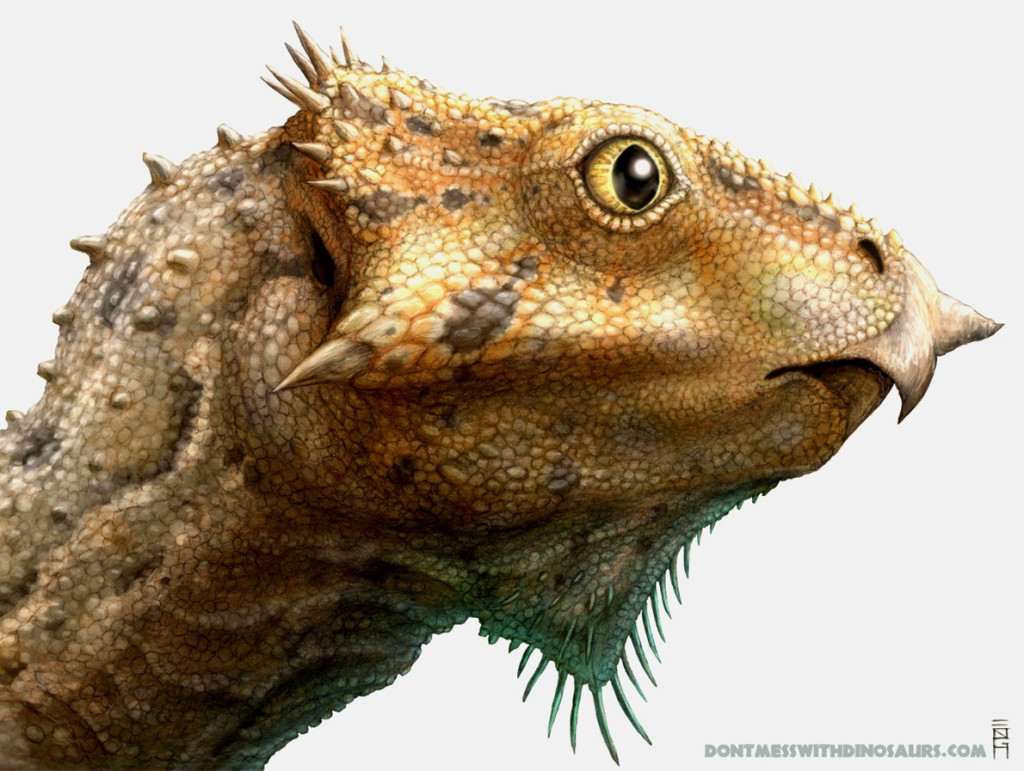

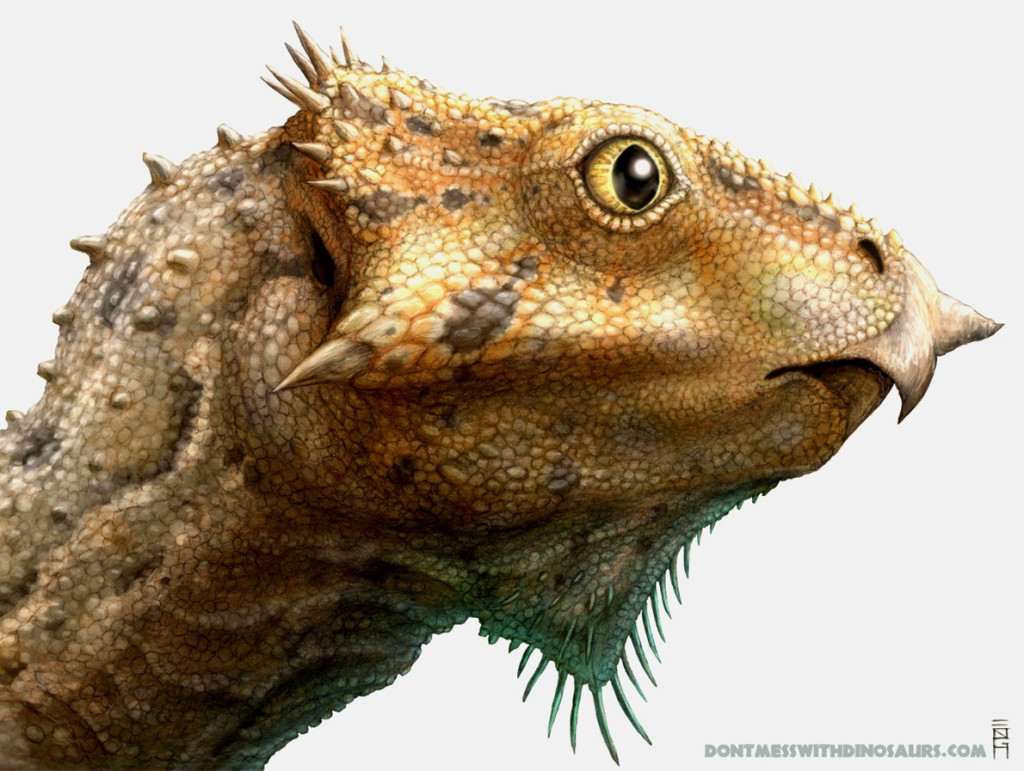

First step was to check out Aquilops‘ smooshed little skull, and also a cast of the much more complete/less crushed skull of Archaeoceratops, which Andy determined was it’s closest known relative. I took a bunch of pictures of both skulls from various angles to help me wrap my brain around how these animal’s heads were shaped. I cannot even express what a huge difference seeing the fossils in person made to my ability to visualize how Aquilops’ skull might’ve looked un-crushed, and how the soft tissues would’ve attached and surrounded it in life.

Based on this personal examination along with Matt Wedel’s skull reconstruction I came up with several rough life restorations of Aquilops’ head, experimenting with various soft tissue displays, thicknesses, and interpretations on the odd little blade of bone sticking out of Aquilops’ beak. While I’m at it, big shout out to Dave Hone for posting up high-res images of this exquisitely preserved Psittacosaurus from China. Those stunning soft tissue impressions, along with impressions left by other ceratopsians were extensively referenced when illustrating Aquilops’ skin and other soft tissues. When we had a settled on a look for the fleshed out head, I mocked up an array of possible color schemes.

One of the ideas that influenced our choice of color palette was the idea that horned dinosaur’s headgear likely evolved for both display and defense, so we thought it would make sense if Aquilops had some showy coloration, but not so showy that it would be unable to hide from predators. Accordingly I looked to modern lizards for inspiration on color schemes, as many of them have stunning color displays despite being low on the food chain and able to blend into the right hiding spots. Once a color scheme was chosen, I rendered the full head reconstruction featured in the paper:

While all this was going on, we were also trying to dig up information on the paleoeocology of Unit VII in the Cloverly formation where Aquilops was found, in order to get a better idea of what the world this animal lived in might’ve looked like. I was fortunate to make contact with Nathan Jud, a graduate student at the University of Maryland, and (so far as we know) the only person currently studying the plants found in Cloverly’s unit VII. He supplied me with several images of gorgeous plant fossils he collected, as well as input as to close modern analogues. The fossils record a seasonally dry woodland, with relatively low ambient humidity, a high water table (it was near a lake) and an undergrowth composed of several species of small leafed ferns (see my “field guide” above), as well as a primitive angiosperm similar to modern Ambrosia (Ragweed). The trees were a species of ancient redwood, with cones identical to modern Coast Redwood Sequoia sempervirens and needles identical to modern Giant Sequoia Sequoiadendron giganteum. When I found out from Nathan that the trees were a kind of redwood I got excited because I live in northern California with redwoods all around my house, and I have visited the Giant Sequoias on a number of occasions, and they are both some of the most awesome trees ever. When I met with Matt and Andy we had talked about depicting Aquilops living in a small group near some kind of cover, and I thought it would be really cool to have them using a burrow sheltered by the roots of a fallen redwood, as I have seen various extant dinosaurs (birds), mammals and reptiles use tree roots that way. So I went out and took a bunch of pictures of various root structures, with my flip flops placed on them as a dinosaur stand in/makeshift scale bar.

Once I had a rough composition worked out I sent sketches to Nathan to work out the most reasonable placement and growing modes of the various plants in relationship to the fallen log and the light that would’ve been made available by the tree’s toppling.

Another key piece of the composition is the predatory mammal Gobiconodon ostrami, and the hatchling Aquilops. We thought it would be cool to include a mammalian predator because so often Mesozoic mammals are thought of as diminutive and primitive, yet Gobiconodon was certainly large enough to prey on small dinosaurs, and had highly advanced (and downright scary looking) teeth. It’s jaws were equipped with multi-cusped blade like molars and premolars, and fang-like conical incisors for which the genus is named. While we can’t know exactly what Gobiconodon was eating, it certainly had a mouth capable of processing flesh and small bones, as well as large claws on it’s paws, and a robust skeleton with substantial muscle attachments.

While the hatchling Aquilops and the adults emerging from the shadowy burrow are entirely speculative they are based on what we know about Aquilops’ close relatives. Several growth phases are known from various other ceratopsian species, and they consistently show young with reduced frills and jugal (cheek) horns, and adults with more elongated skulls, wider jugals and expanded frills. Also, we thought it would be a good idea to show a good number of baby Aquilops, as large clutches of young seem to be the norm for most dinosaurs, ceratopsians included. The strategy seems to have been “make a lot of babies and let the predators sort ’em out”, so we thought it’d make sense to show that happening, and by a relatively small mammalian predator no less. After all, in an ecosystem with Acrocanthosaurus, Deinonychus and Gobiconodon, Aquilops was pretty low on the food chain.

Perhaps Aquilops’ odd rostral protuberance helped them to dig and defend burrows, or engage in intraspecific combat. Perhaps Aquilops grew much larger than the holotype specimen, and could thus fend off larger predators. Perhaps Gobiconodon fed exclusively on insects. Ultimately there are many things that we simply don’t know and many things we can’t know, but it is my hope that rather than presenting Aquilops as just another fossil we’ve managed to present you with the fossil attached inseparably to the idea that it was a once-living creature, with instincts, and habits and needs. A character speaking to us, through the record of geology, an unfathomable 106 million years in the future.

Dinosaurs are rad.