Mill Canyon Dinosaur Trackway

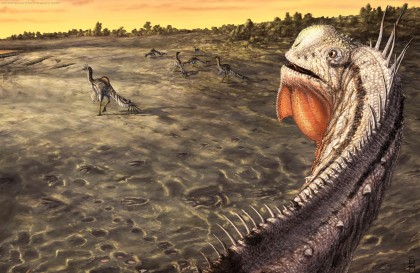

As some of you know, I’ve been doing paleo art work in addition to finishing albums and developing the next Earth Beasts Awaken videos, and I’m excited to finally announce my most recently finished paleo project: an illustration of the Mill Canyon Dinosaur Trackway commissioned by Utah BLM Paleontologist Rebecca Hunt-Foster for an interperetive trail sign overlooking the dinosaur trackways near Moab Utah. Here it is on site.

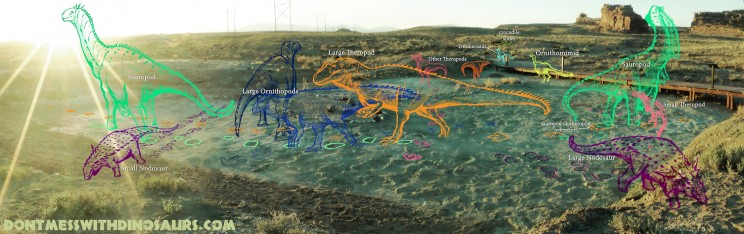

The printed sign you see above is pretty big, 30″x36″ (about a square meter), and the tracks drawn in my illustration had to match the view from where the sign was placed. So the finished illustration had to be really really detailed. In addition to that, the trackway preserves a huge number of footprints from an awesome diversity of animals – at least ten different kinds of footprints and other traces are present – and ReBecca wanted me to depict as many of these animals as possible without making the composition seem to unnaturally crowded, as the animals weren’t likely all there at the same time. Oh, and just to make things extra difficult, basically no good skeletal fossils are known from the same strata as the footprints (the Ruby Ranch member of the Cedar Mountain Formation – Early Cretaceous), so the animals all had to be reconstructed based on close relatives and specimens known from strata a few million years older or younger. All in all this illustration represents my largest, most challenging illustration to date.

In order to reconstruct the panoramic view in my illustration so that it would match the real-life view from where the sign is now placed I had to go to Utah and photograph the site. So I drove out there and camped nearby, and visited the site multiple times a day for 3 days in order to figure out when the best time of day the sunlight was best for viewing the tracks. I found that sunrise was not only the best time to view the tracks, it was goddamn gorgeous and revealed details to me I would’ve never noticed other times of day when the light was higher. So I shot this panorama of the trackway at sunrise, and Rebecca and her husband John Foster (also a Paleontologist) and even their daughter Ruby paced out the best preserved tracks in front of the camera so I could later trace them over my panorama image, which is how I made trackway “field guide” that’s under the main illustration on the sign.

The other reason I was there was to try and make some sense of this intensely complex site and to try to figure out what, of all of it, would be the focus of my illustration. In the process of checking out the site I noticed so many awesome little details that I simply can’t write about it all here, so for now here’s a gallery of some of my favourite tracks:

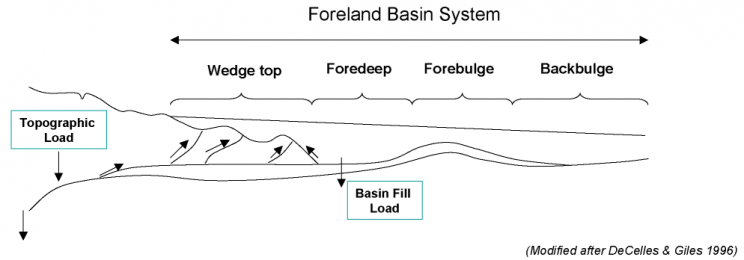

But even after visiting the site, walking that ancient lakeshore, searching for details which might give a clue as to what was really going on there, I still found myself perplexed. What was this environment? Why were the tracks of a huge diversity of animals exquisitely preserved there, while no recognizeable plant fossils could be found anywhere nearby? What were all the big plant eaters eating? Fortunately renowned Paleontologists Dr. Jim Kirkland and Dr. Ken Carpenter offered me some great input, along with Elizabeth Montgomery, a graduate student working on the geochemistry of the ancient lake, and with their guidance the look of the lake and the surrounding landscape began to take shape. Ken and Jim explained most patiently to me that the tectonic activity in the area hadn’t yet produced any mountain ranges or big rock outcrops that would be visible in the background as they are in modern times, but the tectonics further west did play a role in forming the lake. It appears that the lake was in a foreland basin, which is basically the gradually sloping wash of sediments that forms behind a mountain range that’s being pushed up by tectonic activity.

The lake, it appears, was the lowest point for many miles around, and at around 20 miles in length was likely the largest body of permanent water in the area. The ancient sediments in the area indicate a fairly arid environment, perhaps something like the dry open savannah in modern east-central Africa, which might explain why animals were converging on the shore of the lake. Perhaps most interesting though, is that Elizabeth’s geochemical analysis indicates that the lake was likely semi-saline with a unique alkaline water chemistry that caused it to precipitate dolomite, which is basically dissolved limestone, and that combo of dolomites and clay and algae on the shore of the lake made for a particularly resilient concrete-like mud that baked in the desert sun as the lake’s water level dropped, then became harder than the surrounding stone when it was eventually buried in sand by a big flood. According to Elizabeth’s work, there are only two lakes today with a similar water chemistry to that ancient Dinosaur lake: Lake Changara in the altiplano of Chile, and Bosten Lake in China.

Both of these lakes have something really interesting ecologically going on. Despite being semi-saline, lots of animals visit the part of the lake where fresh water flows into it, because the fresh water pushes a lot of the salt and lime deeper into the lake. The fresh water and rich nutrients mixing also support a profusion of soft water plants and algae, which feed various animals (and which may not fossilize readily). Intriguingly, while tracing the layer of rock that forms the lake shore I got the distinct impression that there may have been an inflow channel just alongside the most concentrated area of dinosaur tracks and crocodile slides…

Could it have been that the animals were converging on the one spot where they could find fresh water and perhaps even some aquatic salad during the dry season? While we may never know every detail of this ancient lake’s ecology and geology, it’s nonetheless awesome to be able to visit a place where you can still see the very specific movements of individual animals that lived and died over a hundred million years before our time, recorded in the landscape before you. I strongly encourage any of you who might happen to visit Moab Utah to check out the Mill Canyon Dinosaur Trackway. I don’t think you’ll be dissapointed by all the work ReBecca and a handful of other paleoartists including Mark Witton and Jeffrey Martz and BLM staff put into the interperetive trail around the site, and if you’re tuned into the landscape and what it’s telling you, I gaurantee you’ll be blown away by some of the things you’ll see recorded in the mud of that ancient lakeshore…