Nightmare Mouths of The Permian

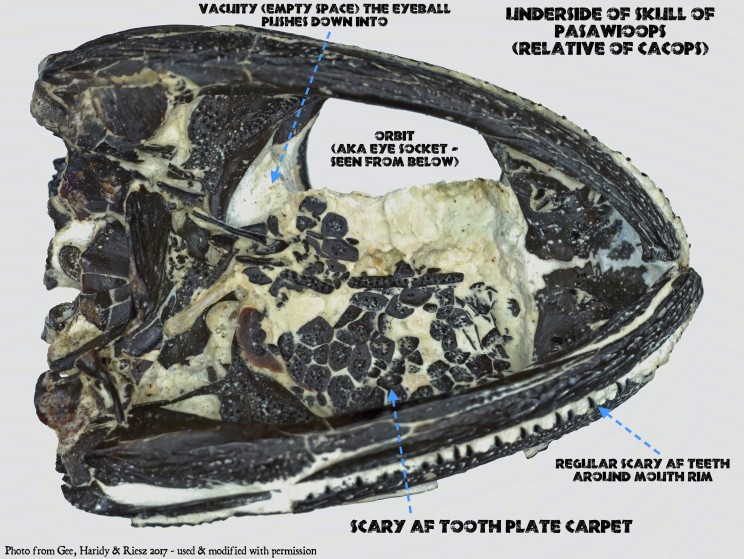

Did you know that some prehistoric amphibians have terrifying teeth covering the entire roofs of their mouths?? Prehistoric monster teeth experts from the University of Toronto Bryan Gee, Yara Haridy and Dr. Robert Reisz have determined how the bizarre teeth covering the roof of the mouth of some prehistoric amphibians such as the chihuahua sized Cacops pictured above developed. It turns out, all of the thousands of tiny teeth these bizarre creatures used to capture and perforate their prey were made of the same ingredients as the teeth around the rim of their mouths, but bizarrely these teeth are not on the jaws, but rather on tiny plates of bone embedded in a flexible layer of tissue on the roof of the mouth. To make things extra nightmarish these tooth-carpets covered empty spaces in the roof of the mouth that their eyeballs would push down into when they swallowed, just like a modern frog. Except unlike a modern frog their eyeballs pushing into their skull would press the teeth down into the prey like a godawful amphibious iron maiden that can swallow you (if you’re a small animal).

You can read and download their scientific paper for free here (shoutouts open access!)

https://peerj.com/articles/3727/

And you can check out the University’s official press release with a video of David Attenborough feeding a bug to a giant monkey frog (with psychadellic skin secretions btw).

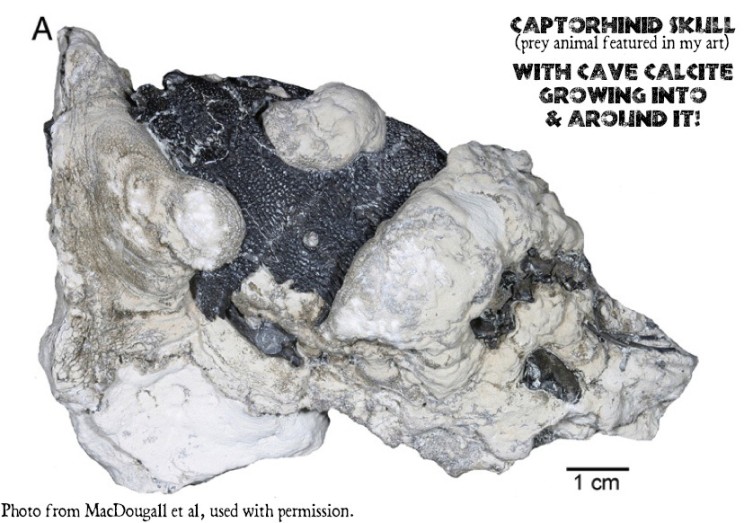

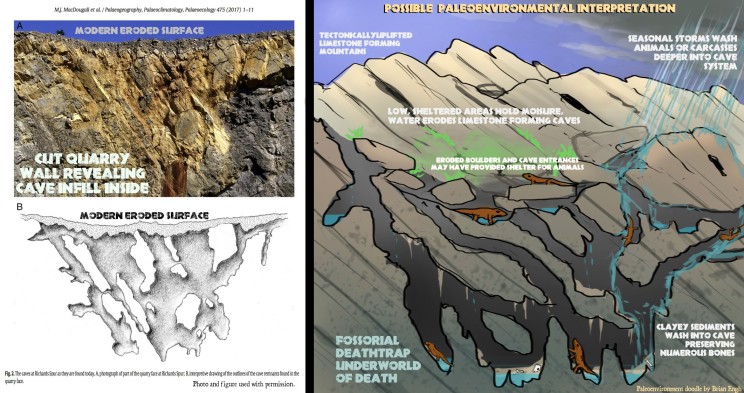

One of the things that really hooked me (puns intended) into doing this quick reconstruction of this wondrous little horror from deep time was the environment. Mark MacDougall et al 2017 describe the strange depositional environment that the skeletons of the creatures pictured in my reconstruction were found in. Turns out these fossils were deposited in an ancient limestone cave system, and some of the skeletons were found with calcite cave formations grown into and around them!

It’s unclear at this point whether the animals were actually living in the upper parts of the cave and got trapped deeper down, as well as washed in by seasonal storms from some outside environment, but the area around these caves in the Permian would have been semiarid, so we thought it was reasonable to speculate that these armored amphibians would’ve been hiding amongst the limestone boulders and crevices that were likely found around the entrances to these caves.

A few months back I just so happened to be exploring a similar modern environment in Nevada, where upthrust limestone has been eroded by water to form numerous caves of various sizes.

One of the things that struck me was how much cooler and more moist the caves were than the surrounding desert – even just a few feet within the entrance. I also found evidence of animals using the caves, from birds and small invertebrates to mountain goats and puma, who had littered the floor of one of the larger cave entrances I explored with a thick mat of goat poop and goat skeletons, one of which had been recently fed on by a puma.

Thus I thought it would make sense to show a similar dynamic happening at the entrance to a small cave in the permian, with both predator and prey utilizing this uniquely productive micro ecological space to survive in a harsh desert environment…

Just a reminder that if you are time traveling and exploring small limestone caves in Oklahoma about 289 million years ago, be careful when putting your hand into small crevices. A Cacops biting you would feel like the world’s slimiest/toothiest bear trap clamping down on your hand and mashing it’s toothy mouth-roof into your flesh by pulling in its damn eyeballs.

REFERENCES, YO:

Gee, Bryan M., Yara Haridy, and Robert R. Reisz. “Histological characterization of denticulate palatal plates in an Early Permian dissorophoid.” PeerJ 5 (2017): e3727

MacDougall, Mark J., et al. “The unique preservational environment of the Early Permian (Cisuralian) fossiliferous cave deposits of the Richards Spur locality, Oklahoma.” Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 475 (2017): 1-11.

David Marjanovi? on 19 Sep 2017 at 6:01 pm #

That’s actually normal for osteichthyans. The oral cavity of *Eusthenopteron* was completely covered in denticles, toothrows and tusks: palate, inside of the lower jaw, bottom of the braincase, gill bars, everything. The ancestors of mammals, crocodiles, birds and turtles have – separately! – lost all teeth that aren’t on the jawbones; many squamates (including all snakes) still have a toothrow on each pterygoid, frogs retain the one on each vomer, salamanders have a toothrow on the vomer and also, before metamorphosis, teeth on pterygoid, the palatine, and the coronoid III in the lower jaw.

What’s special about a lot of temnospondyls (and one colosteid, the “St. Louis tetrapod”) is that many have denticles attached not only to skull & lower jaw bones, but also to completely new bone plates that fill the windows in the palate.

David Marjanovi? on 19 Sep 2017 at 6:02 pm #

My name ends in a c with an acute accent, in case someone’s wondering.

Historian on 19 Sep 2017 at 10:12 pm #

Yeah the insane diversity of tooth morphology is truly stunning and is something that has fascinated me for some time. The goal here was to introduce a broader audience to the idea that Temnospondyls exist and had truly awesome and unusual dentition.

David Marjanovi? on 24 Sep 2017 at 4:40 pm #

But the even more fascinating fact is that their dentition is the usual one, and we are the mutant freaks! :-)

“Morphology”, BTW, just means “shape” here (actually “science of shape”). I’d just say “distribution” to describe the distribution of teeth over jaws and palates (…and plenty of temnospondyls had denticle fields or a toothrow on the inside of the lower jaw, too).

Stefan on 27 Sep 2017 at 10:34 am #

interesting article… but i am wondering, are there animals today with teeth like this? because I dont really see the practicality of a system like this.

layman here.

– Stefan

dontmesswithdinosaurs.com » Nightmare Mouths of The Periman pt. II THAT PREY THO on 07 Dec 2017 at 5:26 pm #

[…] that scary ass amphibian Cacops with spiney lil teeth growing on tiles of bone carpeting the roof of its mouth that I illustrated a […]

dontmesswithdinosaurs.com » 2017 Year In Review on 17 Jan 2018 at 5:49 am #

[…] Between the mastodon mural and rendering the Kayenta timeline I was busy with traveling to paleo conferences, meeting with researchers and museums to initiate projects and doing field work. My biggest journey was a huge road trip from southern California to Calgary Canada to attend the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology meeting. I convoyed up to the great north with paleontologists Andrew Milner, Dr. Jim Kirkland and Don DeBlieux, and had numerous adventures along the way and while there. While in Canada I collaborated with paleontologists Brian Gee and Yara Haridy on a quick reconstruction of some strange permian monsters with especially strange dentition, which you can read more about in my post Nightmare Mouths of the Permian. […]