What in Hell Creek is a T. Rex?

Seriously. What is this animal?

A few months back I did this illustration of T. rex ambushing a Hadrosaur, inspired by evidence that Tyrannosaurs bit the tails of living Hadrosaurs. I decided to keep the attacking T. rex mostly obfuscated by a cloud of dust partially to give the impression that the Hadrosaur was ambushed as its herd stampeded past a hidden Tyrannosaurus, but also because this mighty predator is a mystery to me.

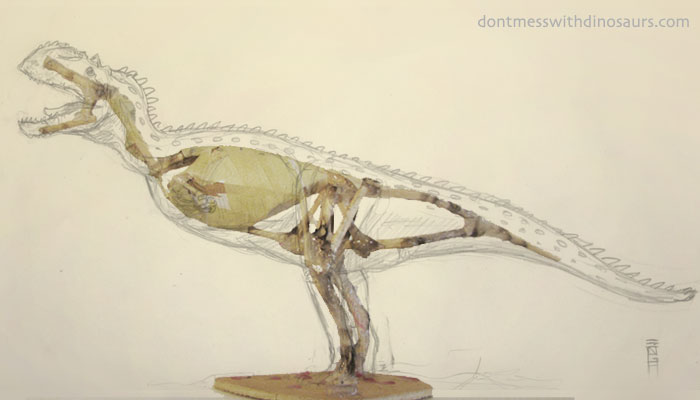

I was recently at the Field Museum in Chicago looking at Sue again in person, and as I gazed up into that huge bizarre skeleton, I could not ignore an unsettling idea prying at somewhere deep in my childhood psyche: This is not Tyrannosaurus Rex. Those bones were from something different. A creature foreign and bizarre to me from a different world. An animal that looked, moved and fought for survival nothing like what I had grown up imagining as Tyrannosaurus Rex.

For a few years now I’ve been trying to come up with a satisfying reconstruction of a big adult T. Rex but I still haven’t managed one, and in my opinion, none exists from another artist. The necks, legs and tails are all too long, slender and bird-like, the body cavity not deep nor tall enough, the arms too developed looking. I feel like every paleo-artist (including myself) is trying to reconcile the actual skeletal proportions of big Tyrannosaurs with the idea of these animals that the film Jurassic Park made so visually concrete and believable. We want to imagine big Tyrannosaurs as agile hunters chasing down their prey, engaging it in combat, and dispatching it with fatal bites. While some of the smaller species of tyrannosaurs, and the juveniles of T. rex may have been relatively long-legged, the really big ones – the ones we base epic illustrations on – simply weren’t. When I look at the skeletons of the big adult Tyrannosaurs I see a hulking beast with a HUGE body cavity, a massive tail and head, and relatively short thick legs. And yet we have evidence that these massive predators attacked formidable living prey. So what the hell is this animal? How did it live, hunt, and sustain its enormous bulk?

In short, I do not see an agile jungle cat. I see something like an obese crocodile on two thick chicken legs.

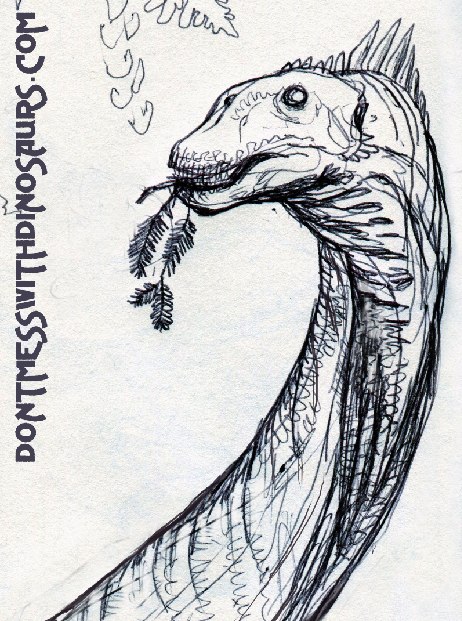

I have been kicking around a few ideas for tyrannosaur illustrations (including a reconstruction of Sue) that I want to do in the coming months as I am able to find the time. I know a feathery body covering to the extent that I have drawn in the above doodle is not likely considering scaly skin impressions of tyrannosaurus have been found, but I have been experimenting with different soft tissue reconstructions with the hope of coming up with some new looks for this old giant. Ultimately my aim is to produce some reconstructions that are true to the fossil evidence while at once dramatically depict this seemingly mythical creature as a something more of a real, believable animal.

I think one of the main reasons why dinosaurs (and other extinct monsters) are so awesome is that we can keep imagining new ways they might have been awesome, and ultimately its a pretty safe bet that when these animals were alive they were more awesome than anything we’ve yet come up with. Nature tends to be pretty kick-ass that way.

Ever seen a fossil nautilus?

Sauroposeidon proteles Reconstructed

Brachiosaurs were big. Maybe too big for camouflage.

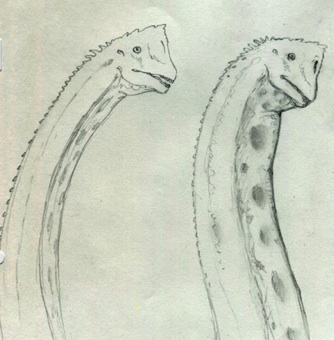

When I look at illustrations of dinosaurs, even very technically good ones, I’m often left with the uneasy feeling that it just doesn’t ‘feel’ like a real animal. Its as if only two simple layers have been added to the still-recognizable skeleton – while living vertebrates often look nothing like their skeletons. This has compelled me to try and push my dino reconstructions beyond just draping skin and major muscle groups over the skeleton. I want to see them come alive, living and breathing beings with muscle, cartilage, circulatory systems, fat, skin, feather, hair, horn, complex eyes, and, as in this case, elaborate display structures.

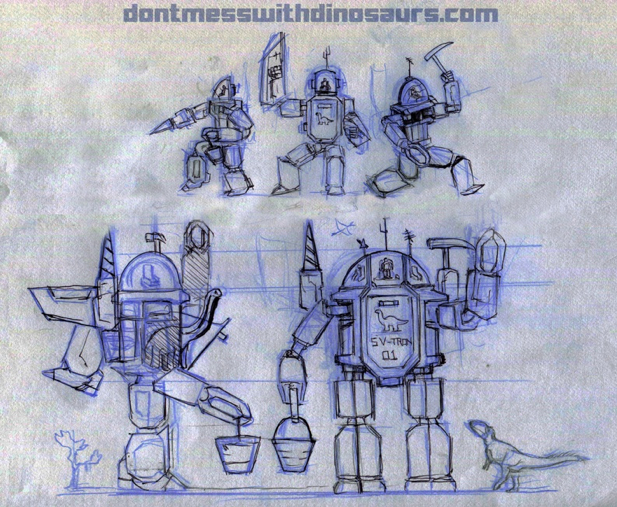

This illustration was inspired by the work of paleobiologists Matt Wedel, Mike Taylor and Darren Naish who write two of the best paleo blogs on the web, Sauropod Vertebrae Picture of the Week (SV-POW!) and Tetrapod Zoology (Tet Zoo). They are also badass paleobiologists who not only dig up fossils and study dinosaurs, but also spy on them, dissect them, and mail order their severed heads to skeletonize them. I have also heard rumors that they are working on a time-traveling three-part combining robot machine and have lazer gunz (this, however is not officially confirmed).

Their blogs contain a wealth of information and discourse invaluable to any artist trying to reconstruct dinosaurs, especially sauropods. On Darren Naish’s blog, Tet Zoo, I found an informative and easy-to-read post describing how to best reconstruct the manus (hands) of sauropods, which I referenced frequently while reconstructing the stompers on my Sauroposeidon.

The elaborate display structures were inspired by various posts on SV-POW from which I learned that sauropods have highly pneumatic skeletons. This means there are air sacs and hollows throughout their skeletal systems much like a bird’s. These skeletal features suggest that Sauropods also had complex respiratory systems, also like those of modern birds. When I learned that, I got very excited, because birds don’t just use their wacky respiratory systems for breathing, they also use them for inflating crazy display structures. With that in mind I did this rough sketch:

Matt Wedel has done a bunch of work studying pneumaticity, especially with regards to sauropods, and he was nice enough to take a look at my rough sketch and give me some feedback:

“I think it rocks. But not nearly enough. Look up some pictures of prairie chickens, hooded seals, singing frogs, and everything else with inflatable display sacs. They don’t look like they just swallowed a stick of Mentos–they look like freeze-frames from half a millisecond after the the detonation of that bomb they swallowed. Real display sacs are so big and so colorful that no other animal could possibly mistake them for anything else. Therefore if you want to draw speculative display sacs they must be so big and colorful that none of the people who see the piece could possibly mistake them for anything else.”

And he’s totally right. Real animals are ridiculous.

Our conservative reconstructions simply don’t do extinct monsters justice. Or, as Matt put it in the same email:

“If you go bold, you won’t be right; whatever you dream up is not going to the same as whatever outlandish structure the animal actually had. On the other hand, if you don’t go bold, you’ll still be wrong, and now you’ll be boring, too.”

Stay Spooky

This is finally done:

A few weeks late for halloween but whatever. November is at least as spooky as October.

Oh, and you can download the .mp3:

The Dark Grove.mp3

(right click to download)

Kilnloads o’ Dinos

Hey so I haven’t posted much progress on my ceramic sculptures because I’ve been really busy finishing them by the firing deadline. Here’s what the loaded kiln looks like:

How many dinosaurs can you find?!?!

Well… in addition to the Majungasaurus I posted earlier I created a similar sized Parasaurolophus cyrtocristatus and a slightly smaller Diabloceratops eatoni (shown here as unfired clay sculptures).

I also created a small brachiosaur model from which I created two rubber molds. From those rubber molds I cast about 25 little brachosaurs…

All of that since last Friday (7/23), with enough time to dry for their first firing by the following Wednesday (7/28). After that first firing the pieces are glazed and/or stained and then loaded into the kiln pictured above for their final high firing (which will turn them into rocks). So yeah, I’ve been real busy!

Here’s my Diabloceratops after being fired for the first time, now with a bit of glaze applied to its horns and some mineral stain on its eyes and back:

What’s this? Two firings? Yeah. Once the clay sculpture is completely dry it is fired for the first time to 1825 degrees. This is called the bisque firing. Bisque firing causes the clay particles to melt just enough to bond the form into a porous terra-cotta like substance. We bisque for several reasons. Primarily, it transforms the brittle dry clay into a more durable substance that is no longer water soluble (unlike clay, which turns to goop when soaked with water.) Also this porous low-fire pottery readily absorbs water. This allows us to apply glazes. Glazes are basically powdered glass, clay and mineral colorants which we mix with water. When we dip or paint or spray this glaze mixture onto our bisque-fired pieces, the porous bisque-ware absorbs the water and causes the glaze particles to stick to the form. Or, as my friend Drew explains it; you know when you throw wet mud at a brick wall and it sticks even after the mud dries? Same concept.

See how the color has changed since before it was fired? It’s going to change much much more. In the second firing temperatures inside the kiln will reach over 2300 degrees F (lava temperature) and the clay particles will become red hot and semi-molten. The form will become denser as minerals vapourize and the clay particles slowly flow together, closing tiny pores and fissures once present in the bisque-ware. Glazes will become completely molten and they will move. The mineral colorants in both clay and glaze will go through the complex chemical reactions that will ultimately give them their final color. And each firing it is a little different. Subtle variations in the chemistry of both the piece being fired, and the kiln environment it’s being fired in can have drastic effects on the look and feel of a piece.

Even the most ancient and experienced ceramists will acknowledge that the results of a firing are never completely predictable. As the kiln door closes we must let go of our work in this final crucial stage of its development to mature without us. If we have not done our work well the laws of physics which govern this art will show us what we have actually created. And if we have done our work well, with attention to detail and upon good instinct, our sense of aesthetics will speak through the form, sometimes in unanticipated and surprising ways.

Now, we can only wait.

Armatures

It occurred to me that it might be cool to make dinosaurs out of different ceramic clays and fire them unglazed so that the natural texture of the clay gives the dinosaur its scales, while at the same time being raw and geological.

So, I’m trying to do that.

I just finished the wood/paper armatures. An armature is any structure made to support soft clay from within. In this case ceramic clay will be built up around the wood. The wood will provide the clay the support it needs until it dries and can support itself. Once it has dried it will be fired and the wood will burn out, leaving the form partially hollow.

I’m dong a Parasaurolophus cyrtocristatus. Ever since I was a kid I loved Parasaurolophus tubicen, but I think the smaller crest on the cyrtocristatus species would be less likely to get broken when the clay dries. I’m planning on doing the Parasaurolophus in a fine grain clay, possibly a porcelain, partially because I think they’re really elegant looking animals, and partially because it is known from fossil skin impressions that Parasaurolophus had fine granular scales.

I’m also doing a Majungasaurus. I love how gnarly and mug-faced the Abelisaruids are and I think their super short forelimbs might also stand a better chance of surviving drying and firing than the more elongate forelimbs of other theropods. I chose Majungasaurus because I think all the weird knobs and horns and mangled boney protrusions on Majungasaurus’ skull will make a lot of sense sculpted in a coarser clay with lots of sand and chunks and mineral impurities in it.

Anyway, I’ll post updates as these guys come to life. I love the transformation that occurs when a clump of wet clay takes form, dries, is fired, stained/glazed and is then re-fired at high temperature to crystalize and turn to stone. I’ll do my best to share that transformation with you.

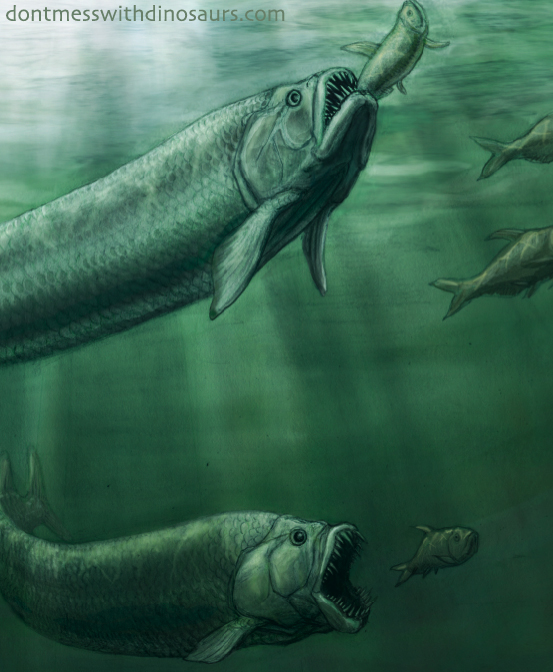

PREHISTORIC TARPON ATTACK!!!!!

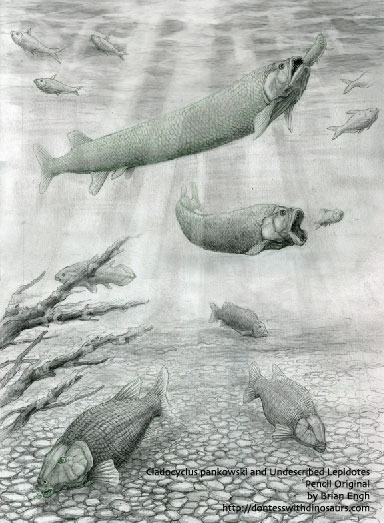

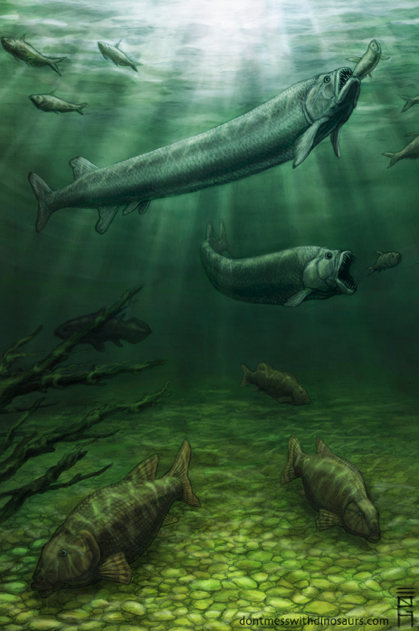

Kem Kem revisited: Cladocyclus pankowskii predates on Diplomystus sp. as undescribed Lepidotes(?) forage for aquatic snails on the bottom. Illustration by Brian Engh.

Did you know that you can buy undiscovered species online?

This piece was commissioned by Mark Pankowski. He buys unusual fossils from fossil dealers and donates them to museums for scientific description. If it weren’t for him the big terrifying fish at the top of the illustration (Cladocyclus pankowskii [named after him!]), and the big ugly fish foraging for snails on the bottom (Undescribed species, possibly Lepidotes sp.) might never have been known to science. Turns out, huge numbers of rare fossils are sold to collectors all the time, and many of them are undescribed or scientifically significant.

Mark found out about me from my Spinosaur illustration which features two Cladocyclus pankowskii. Can you find them?

HINT:

When I did the spinosaur illustration only Lepidotes’ distinctive scales were known from the Kem Kem beds of Morocco (where Cladocyclus pankowski and Spinosaurus aegyptiacus are found), so I reconstructed the Lepidotes referencing the european species L. maximus. The fish featured foraging on the bottom in the new illustration for Mark is based on skull material form the Kem Kem that Mark recently donated and is awaiting description… and it looks very Lepidotes-like. If indeed it is Lepidotes, then it is probably the same species as in the Spinosaur illustration.

If only I’d done the Spinosaurus illustration a few months later!!

Gallery Show!!

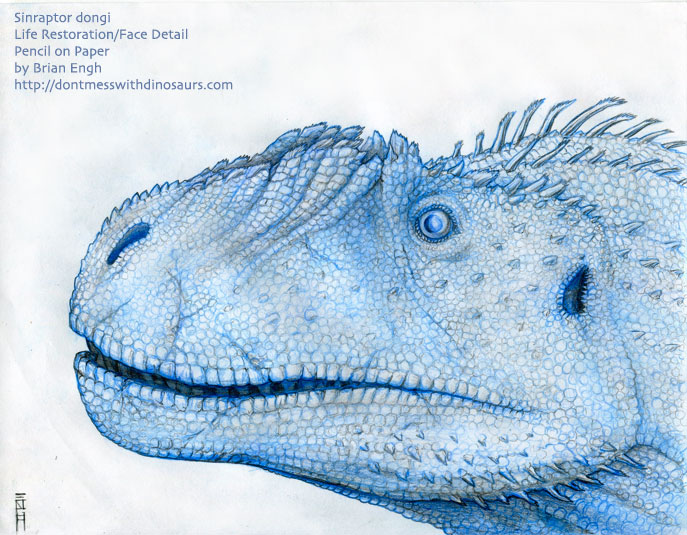

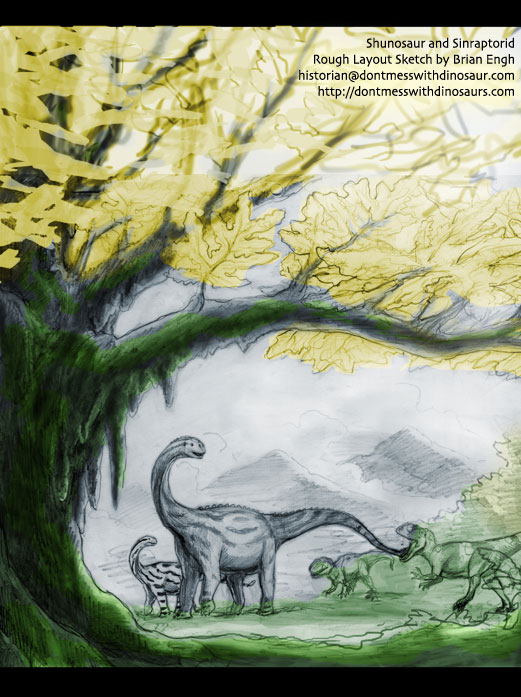

Sinraptor dongi life restoration/head detail. Pencil on paper (to be colored digitally)

I meant to post on this a little while back when my plans became official, but I got carried away drawing and I didn’t. Anyway, I’m doing my first gallery show…

and it’s all paleo-art.

That means don’t mess with dinosaurs. In an art gallery.

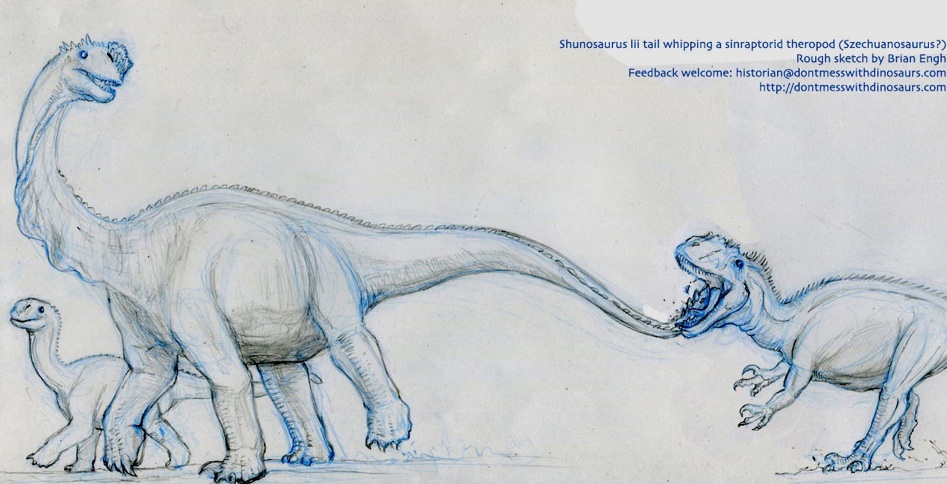

The show is in September so I’m taking most of the summer off to draw dinosaurs and other paleo-monsters pretty exclusively. The gallery is called “The Bone Room Presents” and it specializes in natural history art. It’s located in Berkeley California, so if you’re in the area between the dates of September 2nd to October 5th I hope you’ll stop by. In the meantime, I’ll try to keep up with regular posts of rough sketches and finished pieces as I work through them. Here’s a rough layout of an illustration I’m doing of a Shunosaurus defending its young from some basal Sinraptorid theropods (“Schezuanosaurus zigonensis?”):

The big tree on the left will be a Ginkgo yimaensis, once it is fully rendered. The big weird things hanging from the ginkgo’s branches are called “chichi” (breasts) in Japan. Very ancient ginkgos get them and I thought it would be cool to draw a huge gnarly ancient tree… With breasts.

Anyway, I’m aiming to finish between 10 and 14 new full color illustrations, and I will be showing both the pencil on paper originals as well as prints of the digitally colored finished pieces. I’m in contact with a few paleontologists too, and they’ve been really helpful giving scientific feedback on some of my rough sketches. In that regard, I’m sort of in a ‘pre-production’ phase right now, doing tons of research, amassing reference and getting feedback from experts on my rough sketches in the hopes that everything I produce is as scientifically accurate as possible.

Speaking of which… if you are a scientist who is interested in having a life restoration done for a species you’re working on (or you know of a colleague, friend or enthusiast who is) don’t hesitate to get in touch with me either by leaving a comment or by emailing me directly

(preferred). I figure it’s more worth my time to produce a series of illustrations that will both be seen in my show as well as serve another purpose, scientific or otherwise. Take this piece for example:

I’m just finishing up this commission for a fellow named Mark Pankowski. He donated the type fossils of the fish at the top to the Smithsonian. The Smithsonian then sent the fossils off to Dr. Peter Forey at the Natural History Museum in London. When he determined that the fossils represented a new species of prehistoric tarpon of the genus Cladocyclus, he honored Mark’s contribution to science by calling it Cladocyclus pankowski. The pencil on paper original and a colored print will go to Mr. Pankowski, and another color print will be shown at my show in September. The colored version is very close to finished and I’ll be posting it very soon.

Thanks for checking in! If you want to leave some critical feedback or if you just want to nerd-out about your favourite prehistoric monsters, I encourage you to leave a comment. Or like, five. I get way amped when I get comments.

Seriously. I draw all day and I don’t get out much.