On making a living as a professional paleoartist

At the start of years past I’ve written review posts showing the art I made in the previous year, but when I sat down to do that this year something else started to take shape. If anything, 2020 and especially 2021 for me were distinctly characterized by working with teams of artists to accomplish paleoart projects far larger than I could have possibly completed by myself.

I’m proud to say that the projects I executed were funded well enough that everyone who worked with me was paid a decent living wage, and I kept my cohort busy for many hundreds of hours through a difficult year when a lot of people needed some extra cash to carry them through. I wish I could have hired and paid out even more, but I’m really happy that paleoart projects I landed helped keep artists other than myself busy with paid work. I also realized that with the completion of this fiscal year, paleoart has been my primary income for more than 5 years, and I have seen financial growth every one of those years.

This is not how pursuing a career in paleoart was supposed to go though.

When I was starting work on my first pro paleoart commission in 2014 the narratives from both new and veteran paleoartists were all about how impossible it was to survive as a full-time scientific paleoartist. Even my most stalwart supporter Dr. Matt Wedel told me something along the lines of “all the paleoartists I know have a day job, but that isn’t to say don’t go for it.” I definitely heard that first part of that statement loud and clear, and I would continue to hear similar sentiments echoed by other paleoaritsts for years to come.

But successful artists for whom paleoart made up a significant or primary portion of their paid work were out there, they just weren’t the most vocal people on social media. James Gurney had been sharing his insights and process for years. Julius Csotonyi had risen to a preeminent level in the art form and his work seemed ubiquitious in exhibits, books and magazines. And sculptors such as Gary Staab always seemed busy with huge ambitious projects. If I could elevate my skills to where I could produce art of a similar quality, could I too eke out a living? Or would I be stealing commissions from these great artists I looked up to? Naturally, I wasn’t sure, but I’ve always been passionate about nature, and I find the art & science of prehistoric life fascinating to learn about and fun to create. Also, back in 2014 I was living on an extremely lean artist’s budget and wasn’t really happy with the work I was doing in the entertainment industry, but I figured I could always fall back on entertainment industry gigs if decent paying paleoart commissions couldn’t be found. What did I have to lose?

So I went all in on trying to get more commissions in paleoart.

It wasn’t easy, but by 2016 I was working on paleoart full time, and it has been my main focus & source of income ever since. At the time of writing it’s looking like I am already booked for most or all of 2022. I am also happy to report that more of my paleoart jobs are coming in the form of video-making projects, which is rewarding because I have always considered myself a storyteller and filmmaker first, and an illustrator second.

But how did this happen? How am I still here, 8 years on, doing paleoart full time for 6 of those years, and not impoverished? I ask myself this with some regularity, and I get asked this _all the time_ on my youtube and other social media channels. So, how does one become a professional paleoartist?

I want to see talented artists enrich and elevate this developing art form, which I feel is on the brink of emerging into a period of broader awareness and interest among the general public. So instead of recapping last years projects (again) I started writing up some of the guiding practices that I think have helped me to develop & sustain a growing professional business as a paleo artist.

Before I go any further though I have to acknowledge that my clients who have gone to bat for me to find funding and create opportunities to keep me busy are a HUGE part of the equation. It cannot be overstated that most of my clients didn’t just shoot a few emails and hire an artist, they made a case to those who control funds at their various institutions or granting agencies to hire a professional paleoartist. In many cases I was fortunate that they made the case for my work specifically. The efforts my clients together made it possible for me to develop the skills that continue to pay the bills, and several of my clients hired me multiple times over the years, which has lead to amazing experiences in the field and the development of life-changing friendships. My huge thanks goes out to all of my collaborators & scientific advisors. I also need to give a shoutout to my patreon supporters who have helped keep the budget balanced when the unexpected challenges of complex art projects cause things to take longer than expected. I also am forever indebted to my hard working and supportive family, who have welcomed me home when my life was falling apart in 2015, or whenever I just needed a place to crash between jobs & living situations. I recognize that having that safety net is a huge privilege and my art has benefited from it greatly.

That being said, here are some recommendations to paleoartists based on things I have been doing that have helped keep my art business busy and growing. Sorry if the order of this list is a little weird. I put these in order of imporance first, then reshuffled a few of them further down so that it flowed from one idea to the other better. But these first 5 are the most important by far.

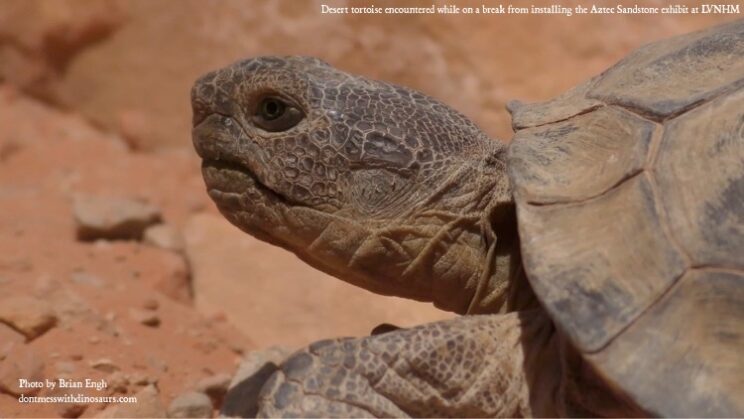

Go outside

Every decent composition or novel idea I’ve ever had for a piece of paleoart has come from spending time in nature. If you want to visualize ancient ecologies you need to be a naturalist in our living ecologies. I believe that paleoart at its core should be an excercise in attempting to learn from, appreciate, and spread appreciation & respect for nature. A lot of paleontologists, collections managers, natural history magazine authors, and exhibit designers also spend a lot of time outside, hiking, photographing, hunting for fossils etc., which means that many of them have also developed innate instincts for what nature looks like. This makes them discerning clients. Successful professional quality paleoart needs to appeal to the most discerning viewers. Honor nature with your artistic efforts, and those who honor nature with their own efforts will recognize what you’re trying to do.

Also, in my experience, participating in field work in both field biology and paleontology has been a huge source of inspiration for me, but I recognize that this is impossible for some people in some financial or physical/geographic situations. That said, if you are interested in participating in field work, get in touch with your local museum or nearby universities about volunteer opportunities. If you cultivate relationships and/or demonstrate your value as a person who puts in work and is willing to learn new skills, you may find yourself with opportunities to help out in the field that cost you no more than your time and energy.

Practice your craft and try to improve and innovate in your art every day

I cannot stress enough how much art fundamentals matter. If you want to be a professional artist it’s a really good idea to practice constantly so that you get at least as good as other pro artists in the field you want to work in. This does not mean copy them though. This means develop your style and your perspective to a level of quality and uniqueness that it is undeniably yours, and undeniably beautiful. If your art is unique, eye-catching, beautiful to look at, detailed, has great composition, and clearly took significant skill to execute people will be more likely to hire you and more likely to pay you what you need to live. It’ll also just be easier to enter a conversation with an expert if you work clearly reflects a dedication to your art and a willingness to do hard work that working professional scientists can see and relate to. My first paleoart commissions were from people who basically said “hey cool arts” which opened the door to me asking them questions, which lead to conversations, which (eventually) lead to commissions.

Ask (politely) to be paid what you’re worth, and explain your financial needs to potential clients

Figure out your daily/monthly/yearly expenses and approximate work time for a piece of a given size/level of detail and charge what you need to in order to cover your expenses + whatever extra you can get to hold you over until the next commission. To put it bluntly, a client that cannot cover your daily expenses is not worth a day of your time. They need to do the groundwork to come up with the funding to hire a professional artist. That said, do not be rude to them, even if they reveal they have no idea what it takes to stay afloat as a professional artist.

As has been bemoaned by many illustrators and paleoartists, artists who subsidize their art by other means of income (or family support) can sometimes undercut professional artists who survive solely on their art. Perplexingly enough, the people most vocal about this issue are sometimes the same people perpetuating the problem. This seems especially true in paleoart, where even skilled artists will post “commission menus” advertising breathtakingly low rates for complicated illustrations. Why you would show how low you’re willing to go from the outset of a business transaction is completely beyond me.

In my experience the concern about professional artists being price undercut by amateurs is in fact over-inflated. Not that it doesn’t happen, but I do not think it’s what’s holding artists back. From what I’ve experienced first hand, the famine mentality in paleoart is due primarily to the fact that paleoartists are simply not asking for enough money to actually sustain an art business. All too often artists are so flattered that a client (especially a renowned paleontologist or big fancy museum) wants to pay them anything to work in an artform they’re passionate about, they agree to doing it for far too little money. But that big fancy museum or paleontologist probably has the money to pay you what you’re worth.

I think it’s extremely important for artists to understand that if you have developed a style or perspective that is unique to who you are as an artist and a client approaches you, they’re approaching you because they want to hire you. Let me say that again for the kids in the back whose teachers are constantly telling to stop drawing during boring ass classes like English literature (where kids are taught the totally un-marketable skill of analyzing the the work of successful creatives): young artists, if you are being true to yourself and making high quality art that is in your style and from your perspective, clients may want to hire you.

If a client wants to hire you, that means when they say “We have a budget of $500 and would like to commission one of your full color highly detailed illustrations” it is completely reasonable and within your power for you to reply “I would absolutely love to do this commission because I am really interested in how _____mastodons did ______ to ____’s ___holes, but given how much detail and research I put into my full environment scenes to ensure that every plant and animal is appropriate and well reconstructed, that piece will take me at least 3 weeks of full time work to complete. As such I can’t afford to do an illustration at full detail for less than $___(3 weeks of expenses + extra to survive + a little extra in case they try negotiate you down a bit).” If you are the artist they want you can and should ask for what you’re worth. Sometimes they wont have the money, that’s OK. If you’re going to be grossly underpaid your time is better spent focusing on developing your unique style that clients can’t get anywhere else.

Oh and look at that, a week or two later another client with a reasonable budget appears and now you’re free to start on their project immediately.

There’s also another cool thing that can happen when you ask for what you’re worth. On more than one occasion clients who approached me revisited their budgets after getting my bid in order to figure out how to find the funding to pay me what I asked for. ReBecca Hunt-Foster was the first to do this for me, and it was incredibly validating. In her case I had even included in my bid that it would be best if I could actually see and photograph the track site in order to illustrate it accurately. Her finding the money thus afforded me the opportunity to make my first field trip to Utah. It was just a few hundred bucks to pay for gas, food and a camp site, but it changed my life. That bid, which I later learned was higher than all the others ReBecca received, indicated that I took my work seriously. I wouldn’t just be painting a few dinosaurs on a track site I’d never seen as a side-job. I would be immersing myself in the research and the field site and trying to do the best site-specific reconstruction I possibly could.

Your commission prices should reflect your worth, and a significant ammount of your worth is based on your intention (and then, of course, your follow through on that intention).

The famine mentality in paleoart is largely a misperception about what clients are actually looking for. Sometimes the main deciding factor for clients hiring an artist is not the artist’s price, but what the artist is bringing to the table in terms of aesthetics, skill, dedication, and willingness to listen to and creatively incorporate the input of the client (and other experts where applicable).

Network, and wherever possible, show up in person

All of these client interactions and communicae mentioned above and following below are made easier, more comfortable and can be practiced more regularly if you network and develop face to face interactions with people. In the pre-covid times that meant showing up in person to museums, national parks, universities, talks, and conferences. In our current weird times that often means setting up video chats or a phone calls. These more human conversations are superior for understanding and getting to know each other and a lot more efficient when it comes to making sketches, asking questions, sharing research refs and sorting out details of projects. Also, sometimes real friendships develop, and those are ultimately more valuable than the few commissions you might work on together.

Work under clear written agreements

Although building face to face relationships and trust is important, you will always benefit from having a written agreement of some form to ensure everyone is on the same page. I also usually send a follow up email right after a productive meeting to summarize key takeaways in writing so that we can reference it later when drafting a final work agreement.

Detail matters

On the scientific side of paleoart, researchers and museum exhibit designers appreciate a depth of detail that at least attempts to pay homage to the complexity of life and the research that has been done to date. Among the general public, a lot of people like to look at art that has a lot of specific details to engage the viewer’s eye. But detail doesn’t just mean carefully rendering each scale or hair in sharp focus (though that is often appreciated by clients), what I really mean by detail is the incorporation of research and both scientific and aesthetic ideas that give images of prehistoric life depth and nuance. In reconstructions of ancient animals it means things like picking colors that reflect hypotheses about life habits or the paleoenvironment, reconstructing soft tissues according to inferences from ecology and modern analogues rather than just shrink wrapping, or incorporating scars or injuries if pathologies have been found in the skeletal record. In paleoenvironmental scenes that detail means getting the plants and bugs and traces and even the sedimentology right. All of these subtle references deepen the sense of story and life history for the viewer, even if they don’t know about the science behind them. And in my experience merely showing a genuine interest in incorporating the research of scientists working outside of “charismatic megafauna” leads to enthusiastic sharing of surprising discoveries and insights that have never been depicted before. This broad incorporation of detail can lead down some really interesting rabbit holes of research and collaboration, which often spark new visual ideas.

Innovate, but with the input of experts

This point may seem pretty strait forward, but it can be tricky. In it’s simplest form, if you’ve already done lots of reading and your research inspires an idea that seems crazy or novel but maybe plausible based on what you’ve learned, do try to reach out to researchers with your question. That said, sometimes experts are very busy and don’t have time to email back, others prefer a phone call. Others might have seen some silly shit you posted on twitter or on your weird website and gotten the impression that you’re an unfiltered lunatic, unprofessional, and/or bafflingly arrogant for going against the norm and presenting your highly speculative paleoart as maybe plausible (gulp). All that is to say there’s some decorum and tact to reaching out to people for input (especially academic scientists) and it can be tricky. Especially bad is if your questions reflect that you haven’t actually done a decent amount of research first (they definitely don’t have time to educate you from the ground up).

That being said, missing a few details and niche scientific papers is totally OK, as long as you’re asking good questions of the right people, not just reading paleoart blog articles & social media groups which sometimes erect and promote hypotheses about paleoart reconstruction without consulting with experts or specialists in the fields of research pertinent to the reconstructions. Often a lot of interesting fossils and insights that can inform paleoart are not published. That said, it is not satisfactory to act on rumor or grainy internet photos, which is why paleoartists need to reach out to and talk to the people that really know what’s been collected, what’s been seen in the field, what’s been suggested in the literature and by whom. Also, it’s good to talk to people in various fields of research to get a sense of who within a given field of research does the most thorough work and is thus broadly respected by their colleagues.

The main thing to remember when reaching out for input on an idea that seems novel or craaaaazy in paleoart is to acknowledge what you don’t know, and pose questions or disagreeing hypotheses in a polite & friendly way. You will soon learn that many experts don’t agree on a lot of things. Embrace the uncertainty, there is room for creativity and interesting discourse there.

Oh and don’t forget to send polite follow up emails. Just because you haven’t heard back from somebody doesn’t necessarily mean they don’t want to hire you. They might just be busy.

Bring multiple products & options to the market

Sometimes a client wants a full color illustration for too little money, but the money they have might be enough for a black and white sketch. Or, sometimes the client alludes to having more money, in which case maybe you can create some animations with the illustrations you make, or maybe do a sequential series of illustrations to tell a story. There are so many ideas to explore. You, as the creative need to share your creative ideas. Suggest things offhand and see what gets your client excited. The more different things you can create, the more likely you will be busy with work.

Work with researchers to develop projects

While it may be true that there are not an over-abundance of people going around with an already established project looking for an artist to hire, there are certainly a lot of researchers who are interested in developing projects with paleoartists. Some of them might not even realize it yet. Building projects from the ground up will necessarily mean more front-end investment on your as an artist, but this can be a really rewarding route to take as your ideas and efforts will help to bring new things into existence that would have never existed without you and your scientific collaborators working together. Again, be the creative, put ideas out there. Don’t wait around for opportunity to fall in your lap.

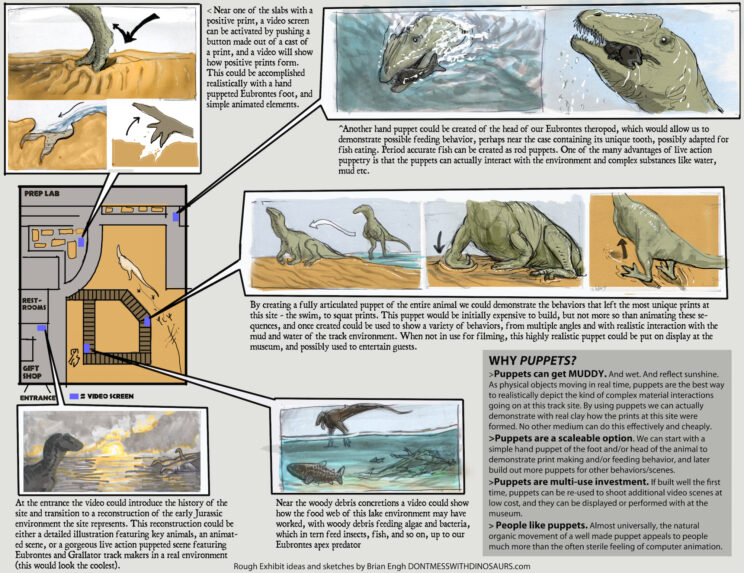

Video kiosk plan pitched to SGDS

Video kiosk plan pitched to SGDS

Develop diverse revenue streams

Here is a list of revinue sources/ways my paleoart has brought in income:

-Grant funding from friends groups and natural history societies

-Museum exhibit funds from museum’s annual budget

-Research funds set aside for outreach & publicity

-TV documentary production funds

-Exhibit funds donated by a private donor outside the museum

-Crowd funding

-Selling my body (i mean for food, to cannibals)

-Petty cash from the descretionary funds of university & museum departments (for small jobs)

-Selling prints at outreach events

-Selling printed stuff like t shirts etc online

-Selling originals

-Licensing art for use in books, magazines, exhibits etc

-Patreon

Develop your own projects toward becoming profitable or at least powerfully promotional

I mentioned before that if a client can’t afford to pay you a living wage you’re probably better off working on your own art. There are always fundamentals to improve on, always new ideas & styles to explore. The stuff artists do for passion often becomes the foundation to a portfolio, a style, a career. That being said, we live in amazing times when artists can actually self fund a lot of stuff. So, wherever possible, look for ethical ways to make some money off of the art you do independently, and try to grow this over time.

Play the long game

Own all your copyrights. Even if a client sends you a contract that says you’ll be signing over your copyright, politely decline that contract and explain to them that you need to retain your copyright because this is essential to your income as a professional artist. I have never had a client decline working with me for this reason. They usually totally understand, and will either talk to their legal department or ask if you have a contract you can send them. One of the handy contract types I’ve used a few tims is called a “materials for use” contract, where the client pays the artist for their time creating the art (aka “materials”) + a licensing fee to use the artists materials. The terms of the license are laid out in the contract. Very few things feel like free money like getting money for art that you already got paid to make. Again, make sure your time writing emails & drafting contracts is covered. At this point I don’t license anything for less than $100, and that is in line with the lower end of licensing fees for some magazines & book publishers.

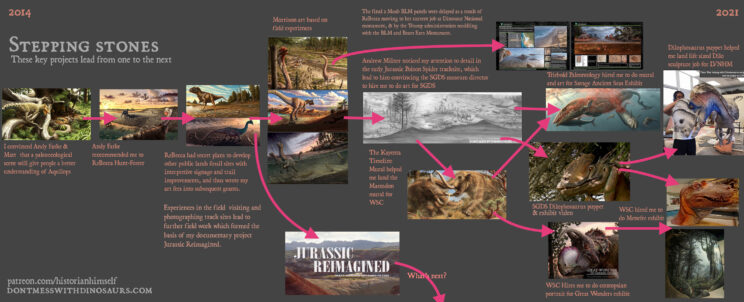

Career stepping stones are also important. Sometimes it’s better to take a job that pays slightly less or the same amount as another opportunity if it steers your career or collaborations in the direction you want it to be going. In this way, the project you’re working on right now can be a stepping stone to future projects. For example, I thought it would be cool to do murals, so I needed to show future clients that I could do a whole paleoecological scene to a high degree of scientific detail. So, I negotiated with Andy Farke and Matt Wedel to do a full ecological reconstruction of Aquilops in its environment rather than just doing a lateral-view head restoration. That lead to doing larger paleoeco scenes for ReBecca, which lead to murals at the Western Science Center. I also want to do practicalfx in my documentaries and films, so I have retained the molds to all my sculptures so that I can cast skins out and make puppets of the animals I’ve sculpted. Aiming for stepping stones is important. That said, you have to ensure your bases are covered financially. I have cut it really close a few times, and even taken some hits financially because I miscalculated how long stuff would take. Fortunately, that’s where having diverse revinue streams comes in to buffer your budget so that if some of your stepping stones turn out to be a bit wobbly (financially) you don’t end up underwater.

Don’t spread yourself too thin

This one is my greatest weakness. People who are passionate about what they do can easily get way too excited about cool ideas and new projects and take on too much at once. I do this. Coupled with the reality that you don’t always know exactly how long a project is going to take, and you can find yourself with smashed schedules and excessive stress, and all of this leads to you not doing your best art work. I struggle hard with this one. It also sometimes signals that you need to raise your prices.

Traditional art is not dead

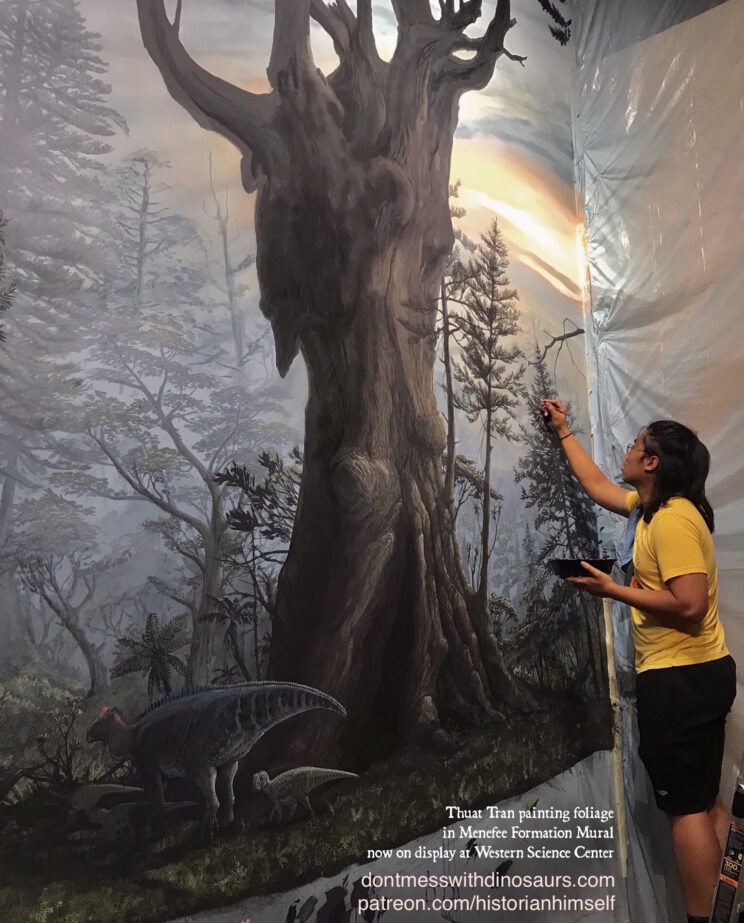

This harkens back to the first point about art fundamentals, but it actually bears saying specificially now that we live deep in the dystopian future where lots of aspiring paleoartists are producing everything entirely digitally (seriously, yall kids should go outside). I feel strongly that my art frequently receives preferential treatment because it is always based at least partially in traditional media (even when the final illustration is digitally colored). I think this is because lot of people are just tired of looking at screens, photoshopped advertisements, CGI, printed billboards and all manner of imagery that all feels just slightly less human that a bunch of paint or graphite or paint or ink smeared on some dead tree fiber or a hunk of clay cooked until it turns hard. People like knowing and feeling that human hands directly interracted with a physical thing, and when you see these pieces of art in person, you can usually see the difference in the art. Digital painting and 3D modeling are powerful tools, but for me they’ve largely become ways to pre-visualize before actually creating the final work partially or completely in a traditional space. Because my digitally finished illustrations are based on scanned graphite drawings. I still own all those originals. I intend on doing gallery shows and selling them when the time is right. (Playing the long game yo)

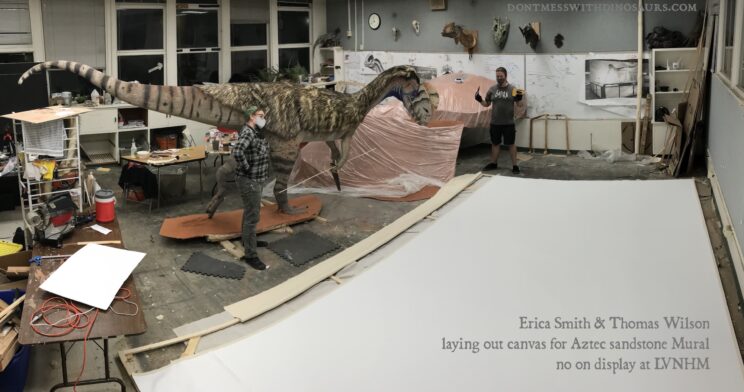

As I’ve moved into doing large scale exhibit art, I’ve learned that aesthetically at least, traditional art scales up better than digital, especially in 2d. Painting a mural in the real physical space where it will be seen by guests makes a huge difference to how the lighting, perspective and composition in the painting relate to the surrounding exhibit space. Oh cool, you toiled on your computer in front of a relatively tiny screen for a zillion hourse to create a high res digital illustration? Well it turns out that when we print it up extra big the resolution will be stretched (really good computers still struggle to handle big mural-sized files at 300dpi). Also, now that you’re here seeing the exhibit opening, one of the things you spent mad hours detailing is obscured by a skeletal mount, and theres a weird shadow on what was supposed to be the highlight in your painting. Oh, also the client had to pay $5000 just to print the mural… How long of a hotel stay + how much paint could that have paid for if you stayed near the museum for a few weeks and actually painted on the wall? Again, it pays to show up in person (even if you do end up executing the mural digitally, as I did with my first one).

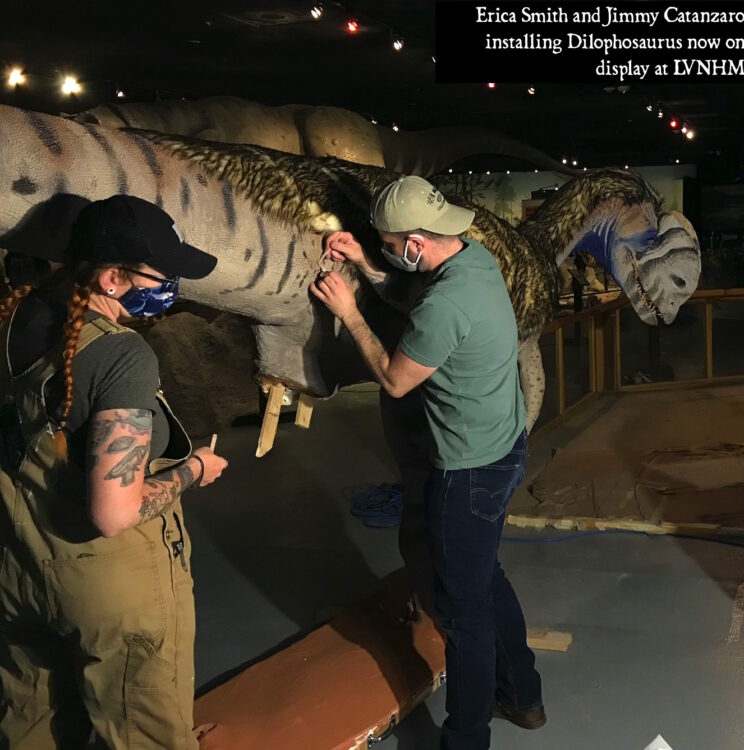

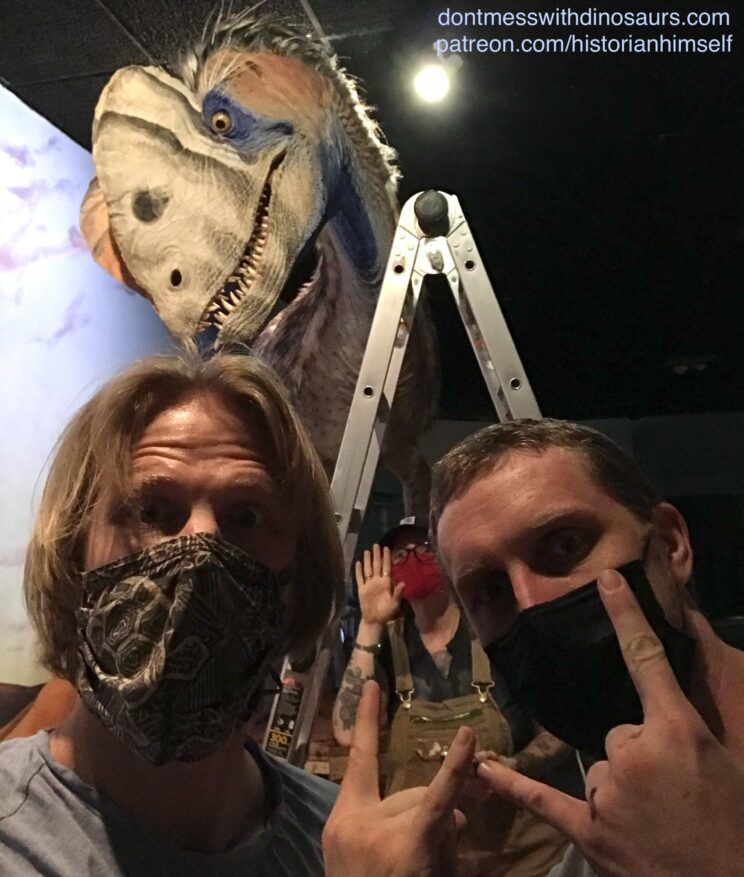

In the case of large scale sculpture CNC milling of styrene has been used on some pretty impressive dinosaur sculptures, but the finer details of the surface textures still have to be hand sculpted. Also fwiw CNC milling of styrene comes with a lot of waste and potentially other environmental concerns. Also, now that I’ve sculpted at both full scale and small scale I’m not convinced I’d be able to predict exactly what the best pose will be in a space based on a small scale model. The Dilophosaurus I did for LVNHM changed it’s pose significantly once I got it mocked up at full scale. Not that my plans at small scale wouldn’t have worked, but being able to adjust it as a full scale poseable framework before locking it in place and sculpting the rest made it work in the space better.

So that’s a bunch of stuff that I thought other artists might find some useful advice in. I hope this makes sense and doesn’t come accross as too preachy or self righteous or whatever. I took the time to do this because I want to see other artists develop and successfully execute professional level commissions in paleoart.