Introducing Mirarce eatoni – the most complete enantiornithine bird from North America

This summer I had the pleasure of embarking on an adventure into the Utah desert to survey some late Jurassic Morrison Formation outcrop lead by Dr. Mathew Wedel along with his colleague from Western University of Health Sciences Dr. Jessie Atterholt. Along the way I learned that Dr. Atterholt studies birds and that she was nearly done describing one of the largest and most complete enantiornithine birds from North America, and she needed paleoart depicting what this big old bird might have looked like. I of course jumped at the opportunity to illustrate a member of the floofiest branch of the Dinosaur family tree. Her paper, describing the skeleton of this ancient bird now named Mirarce is now published, and can be downloaded (for free!) here: The most complete enantiornithine from North America and a phylogenetic analysis of the Avisauridae

For those that aren’t famililar with the various clades of early birds, enantiornithines are a group of early birds known mostly from Asia, which were pretty advanced, and which some amazingly preserved fossils (including a baby encased in amber!) show us looked enough like modern birds that we probably wouldn’t think they looked out of place if they were flapping around in modern times. Like modern birds they had fully developed plumage, the ability to fly, and in some cases big fancy tail plumes… But unlike modern birds their shoulder girdles weren’t as developed for flight, a few species retained claws on their wing fingers and/or teeth in their jaws, and they lived alongside the dinosaurs as far back as 130-ish million years ago!

To date I have done very very few reconstructions of early birds, and all only as peripheral animals in larger paleoecological scenes, so when Dr. Atterholt told me about Mirarce I was happy to learn that enantiornithines had been found in North America, but I was surprised to learn that this specimen had been discovered in the Kaiparowits Formation in the now recently reduced Grand Staircase Escalante National Monument way back in 1992. It made sense that this bird was in North America in the late Cretaceous though, as fossils from Asia and Europe show us that birds evolved at least as early as the late Jurassic, and being flying animals would have been free to spread across both land and sea faster than animals requiring land-bridges to get from one continent to another. In fact the first illustration I was commissioned to do that involved early birds was my reconstruction of the early Cretaceous Mill Canyon Dinosaur Tracksite, which features several speculative early birds which were included because bird-like tracks have been found at the site. The Mill Canyon site dates back to around 112 million years ago, which is around the time that a lot of non-avian dinosaur groups were finding their way into North America, probably via land bridges connecting N. America to Europe and Asia. So if large bodied flightless animals were making their way over, it stands to reason that the flying branch of the dinosaur family tree probably made it over to North America much much earlier.

The reason that not many Mesozoic birds have been found in North America is probably due to some combination of sampling bias (people just looking for big dinosaurs, especially in the early days of paleontology) and preservational bias (itty bitty animals rot, get eaten, or get destroyed by water moving sediments around quite easily, while somewhat larger animals with sturdier bones are more likely to get buried in tact in most depositional environments.) Due to that preservational bias it is perhaps not surprising that despite being the most complete enantiornithine from North America Mirarce is still pretty incomplete.

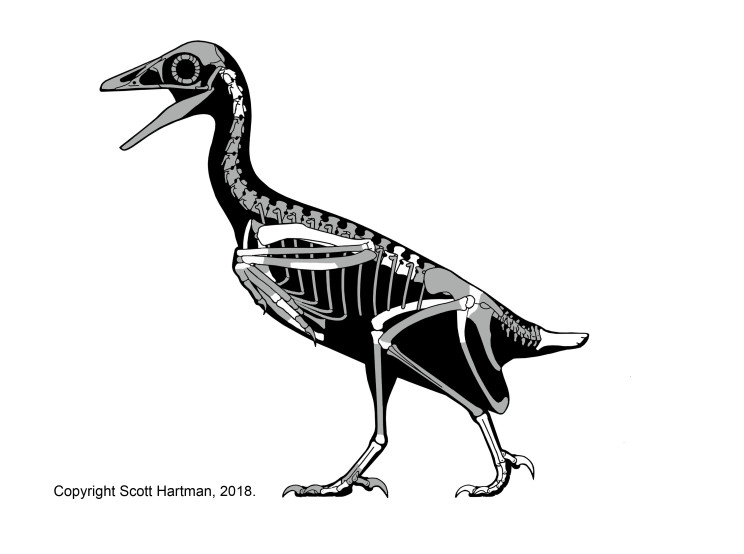

Enantiornithine skeletal reconstruction showing the parts of Mirarce that have been found (white) by Scott Hartmann

Broken and incomplete as Mirarce‘s skeleton is, it being found in North America still shows us some pretty cool things. First of all it was pretty big. Somewhere around the size of a fat raven or a slightly runty turkey vulture, it was one of the largest known enantiornthines, but that doesn’t mean it couldn’t fly. In fact it may have been a stronger flier than most enantiornithines as it had a more developed shoulder girdle which shows adaptations similar to more advanced bird groups, although it evolved these adaptations convergently.

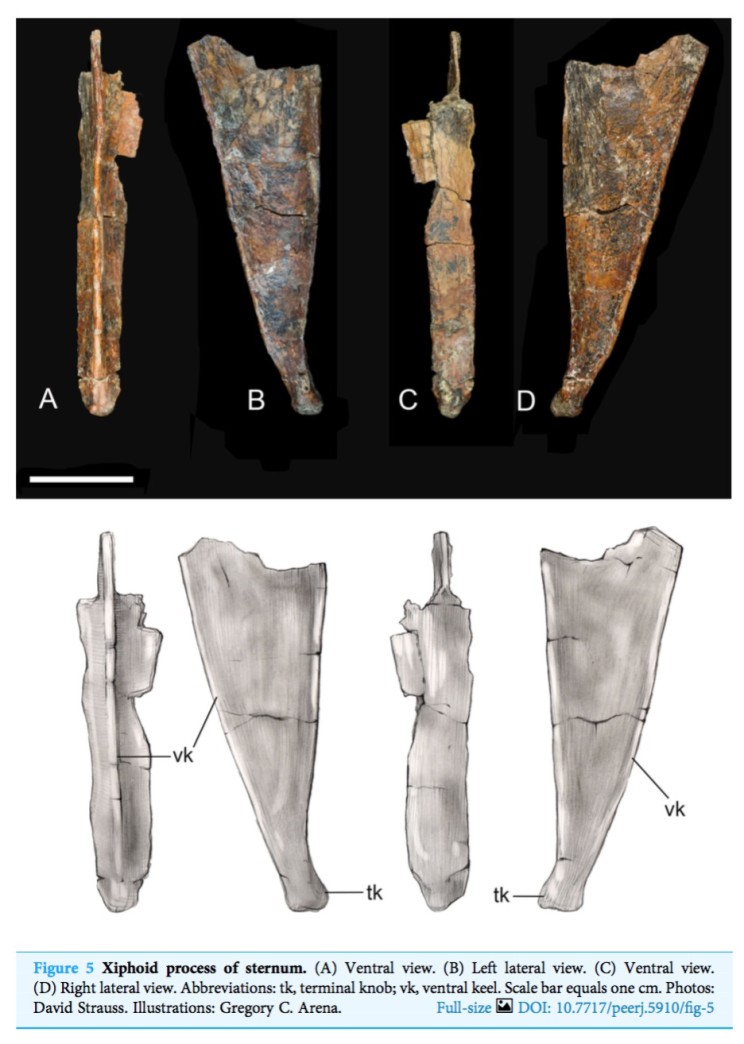

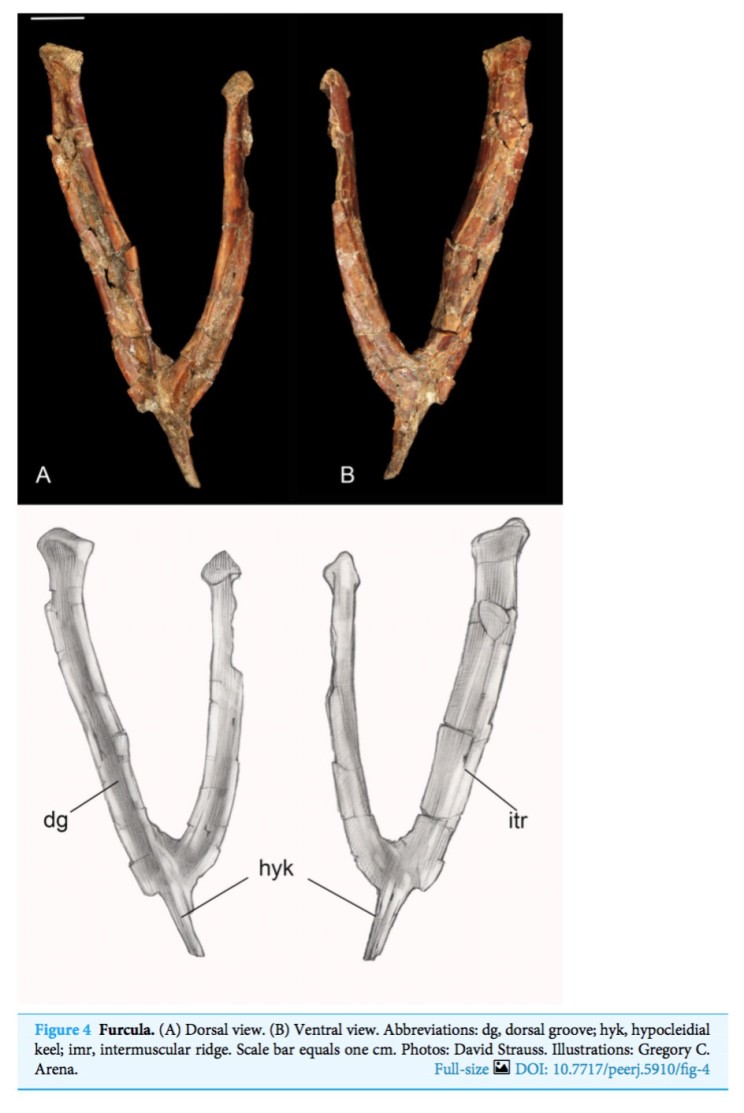

Mirarce‘s nicely preserved sternum (where flight muscles attached) and wishbone (an important part of the shoulder girdle of flying birds). Figures from the paper.

Because of it’s unique features and their similarity to other North American enantiornithines the phylogenetic analysis of all of these early birds indicates that the North American Enantiornthines formed a distinct late Cretaceous clade, perhaps evolving in isolation or semi-isolation in North America once sea levels rose and North America’s connectivity to Europe and Asia were reduced.

While driving accross Utah and camping in dusty sediments of the Morrison Formation, Jessie, Matt and I discussed a few ideas for the art and I made several sketches. For the sake of giving the public an easy takeaway we focused the art on communicating that Mirarce was pretty big and that it lived alongside non-avian dinosaurs. Fortunately the Kaiparowits of the Grand Staircase Escalante National Monument has yielded numerous spectacular non-avian dinosaurs, including the bizarrely ornamented ceratopsians (horned dinosaurs) Kosmoceratops and Utahceratops. I have seen a lot of egrets and other birds perched on or around large modern grazing animals, so I thought it would be cool to show something similar happening with one of the nonavian dinosaurs from the same time & place as Mirarce.

We decided to go with Utahceratops gettyi because it honors the late paleontologist Mike Getty, and also its slightly down turned brown horns seemed like they would make good perches. I did not know Mike Getty personally, but a number of my collaborators did, and I am assured he would have liked the idea of a couple of goofy birds perching (and probably pooping) on the face of his big weird Chasmosaurine dinosaur.

Photo by Tom Stables/The Comedy Wildlife Photography Awards.

Big shoutout to Jessie and Matt Wedel for bringing me in on this project, and shoutouts Scott Hartman for his nice skeletal drawing. Also shoutout the coauthors Howard Hutchinson for finding the fossil, and Jingmai O’connor for being an ancient bird phylogeny master. Jeff Eaton gets a shoutout too because he is the Eaton whose name Mirarce eatoni honors because he did a lot of work in the Kaiparowits Formation where the critter was found.