NEW (really old dead) DINOSAUR!!! Arkansaurus fridayi

Introducing the new early ornithomimosaur dinosaur Arkansaurus fridayi, now formally described by ReBecca Hunt Foster years after its initial collection. I was commissioned by ReBecca to draw some figure art and do a reconstruction of the animal for the paper and press release, and its formal announcement marks the second new dinosaur taxa I’ve had the honor of colaborating with a publishing author to prepare a first reconstruction of. To add to the excitement, this animal has also been officially named the Arkansas state dinosaur. You can find the full scientific paper HERE: Hunt & Quinn 2018 – New Lower Cretaceous ornithomimosaur

We also prepared this life reconstruction with some data on the plants from that time, with some input from paleobotanist Nathan Jud, to try to show the good people of Arkansas what their state might have looked like over 113 million years ago when their now freshly minted state dinosaur was roaming around:

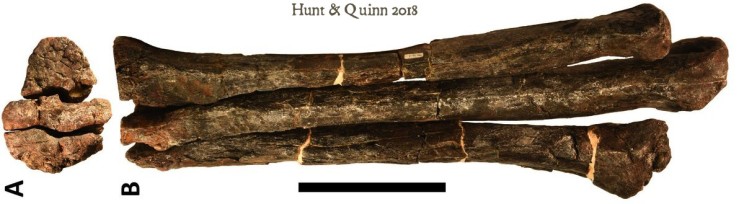

Now if you take a look at the paper or any of the other press images floating around you’ll quickly realize that all we have of Arkansaurus is this:

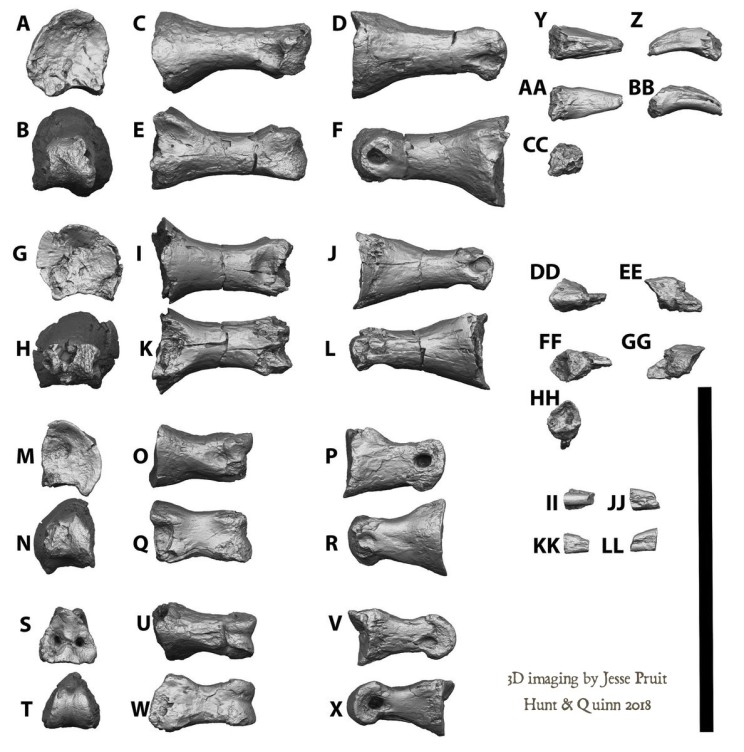

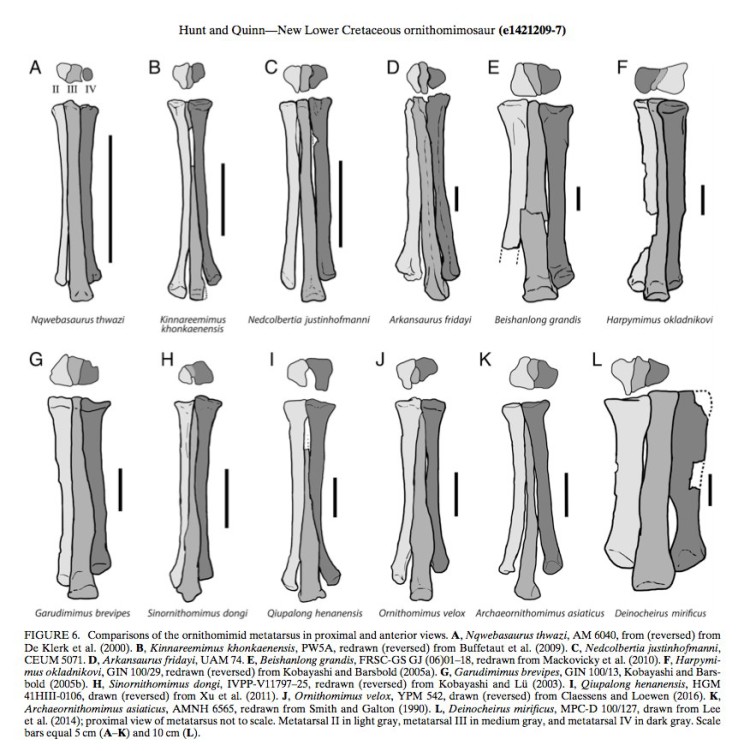

Yep, that’s it. Three big old long skinny metatarsals, and a few smaller toe bones. So when a friend asked “how the hell do you reconstruct a whole damn animal from a partial foot??”, I answered “with a BIG asterix* next to it.” Because quite frankly, all we know is that this foot compares favorably with other ornithommimosaur dinosaurs of similar age… To get a better sense of that comparison ReBecca commissioned me to do these figures of the metatarsals of a whole bunch of ornithomimosaurs:

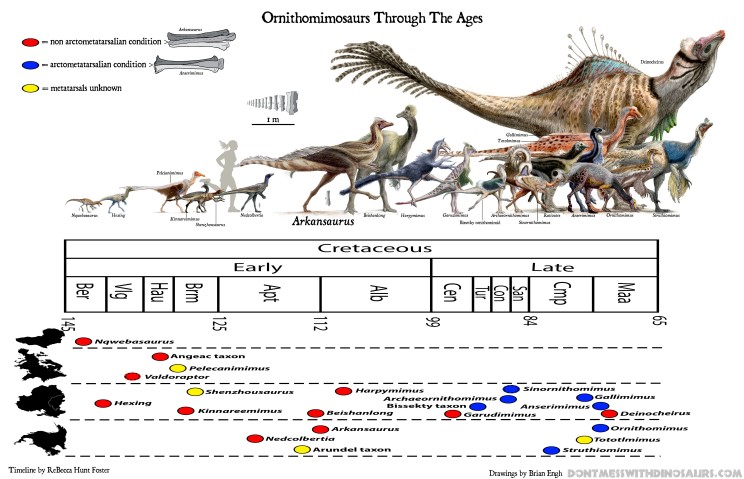

The story of many ornithomimosaurs, like Arkansaurus, seems to be a story of elongating the legs and laterally compressing the metatarsals. In some groups the top of the middle metatarsal is actually pinched in by the other two metatarsals resulting in what is called an “arctometatarsalian condition”, which reduces unneccessary movement in the ankle, thus giving the animal a more efficient stride when running or trotting long distances. Along the way the ornithomimosaurs lost their teeth such that by the end of the Cretaceous all the various known ornithomimosaurs are toothless, and a bunch of them look superficially similar to ostriches and other modern ratite birds who independently evolved a similar body plan much much later.

This overall story towards efficient running (often referred to as “cursoriality”) is a tidy little narrative, that may apply quite nicely to some lineages. But as I was digging through the literature on other ornithomimosaurs something interesting struck me: these creatures aren’t all following that same narrative – NO – these weirdos were ALL OVER THE PLACE, both anatomically and geographically, and for a LONG DAMN TIME! Some of the earliest known taxa had already started laterally compressing their metatarsals, while other later taxa in other parts of the world had much more primitive looser ankles, and some retained this primitive trait well into the late Cretaceous. That realization lead me to take interest in modifying another of ReBecca’s figures – a timeline mapping ornithomimosaurs throughout time, accross continents, and according to the style of ankles they had. You see, I’m a lunatic and although ReBecca’s timeline was very nice, I thought it needed to be taken further. CLEARLY, the only way to reconstruct an animal known only from a bashed up foot is to reconstruct ALL of it’s relatives (OF COURSE).

(click it up big, it’s HUGE)

(seriously. click it up big.)

So check it out – The earliest animal presumed to be an ornithomimosaur is an African animal called Nqwebasaurus and it’s pretty much what we would expect a pretty basal ornithomimosaur to look like. It has four toes, small teeth in it’s mouth, elongated legs, but it’s not arctometatarsalan. What’s interesting about it is that it occurs all the way back in the very very beginning of the Cretaceous at around 145 million years ago, and it’s the only known ornithomimosaur from Africa. Did it originate there? Who is the next closest relative? Where are the other African ornthomimosaurs?? All good questions we don’t have answers to. Shortly after Nqwebasaurus on the timeline is an animal called Hexing, and it’s substantially different, with a more derived looking skull, and it’s in Asia. Shortly after that there are a handful of European taxa that are really really fragmentary (so I didn’t draw them), but what has been found of them has them looking like ornithomimosaurs, implying that by the earliest Cretaceous this group of animals was already substantially diversified and widely distributed.

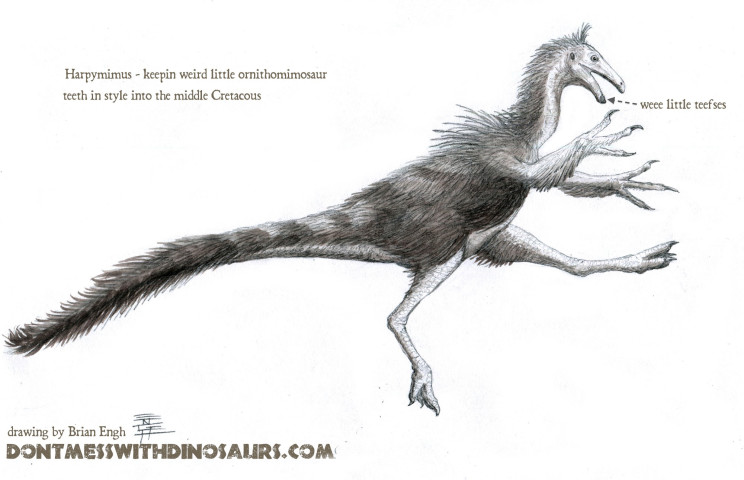

Among the other early ornithomimosaurs Hexing, Pelicanimimus and Shenzhousaurus also all preserve some number of teeth, but the jaw morphology, tooth count, and spacing of the teeth vary wildly. Pelicanimimus, has a damn fine toothed comb in it’s mouth, while Shenzhousaurus has just a few larger teeth in the front of it’s jaws. This seems to indicate a high degree of radiation and specialization even among these early forms. It would be nice to say that none of the later ornithomimosaurs dont preserve any teeth, but this one weirdo Harpymimus has teeth on only it’s weirdly downward curving lower jaw, and it lived after our Arkansaurus, so ReBecca left it up to me to decide whether or not Arkansaurus should have teeth or just a beak (if you look closely in the forest scene I gave it wee little teeth).

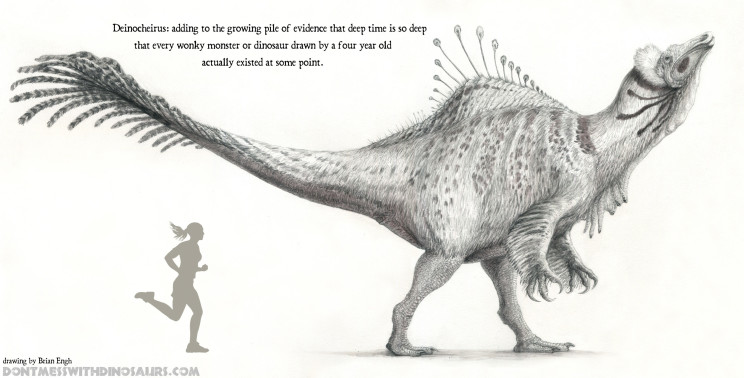

Kinnareemimus is also interesting because while it’s not quite arctometatarsalan it’s damn close, and the legs are pretty darn elongated. It was likely a pretty efficient runner, and occurs way way before the first properly arctometatarsalan animals on the timeline. Then all the way at the end of the Cretacous you have Deinocheirus, a nearly T-rex sized hump-backed weirdo with a broad spoonbill like toothless beak and a totally chunky primitive ass ankle.

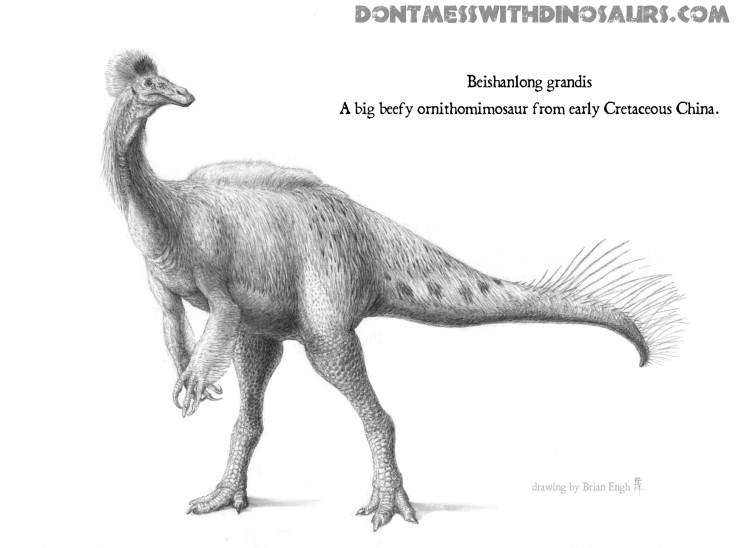

So what does this all mean? One thing is certain: there is an unfathomable ammount of diversity in the fossil record that is still waiting to be found. The sustained diversity in ornithomimids tells us there are certainly huge ghost lineages on multiple continents going all the way back to the late Jurassic in Africa. That is cool. Without a doubt there was a lot of evolutionary experimentation going on, and the possibility of a variety of giant body sized weirdos between Beishanlong and Deinocheirus (who are presumed to be related) is tantilizing.

Another intriguing possibility is that there is some convergence at play. It’s entirely possible that some of the early forms in Africa and/or Asia actually arose from a different common ancestor than some of the later things that also evolved toothlessness and/or long running legs and/or loss of the fourth toe. Unfortunately the fossil record for this whole group of animals is pretty patchy and in the case of things like Arkansaurus, super fragmentary. So when you consider how powerfully convergent evolution shaped modern ratite birds into superficially similar dinosaurs in our modern age, it seems entirely possible that the same evolutionary patterns could have had plenty of time and space to manifest in multiple lineages way back in the Mesozoic.

For me, and no doubt for ReBecca here in north America, it’s particularly exciting to see that a large bodied ornithomimosaur was present in north America as early as 113 million years ago, and implies that right here in north America there is a huge evolutionary story with ties to Asia that is still waiting to be found… Oh, and Arkansaurus or something with feet very much like it left these gorgeous tracks at about the same time at the Mill Canyon Dinosaur tracksite in Utah: